The (New) Collectives Queering Czechia’s Nightlife

Published March, 2025

by Freddie Hudson

The third of a series [read part no 1 and 2 here and here] looking into marginalised communities in the broader Czech music scene, locally-based journalist Freddie Hudson speaks with three community organisers creating club nights designed primarily for LGBTQ+ audiences in order to understand Czech acceptance of gay and queer identity through the lens of local nightlife.

This article was written upon a political backdrop that includes Gisèle Pelicot’s gruesome trial in France, the news that 70,000 European men are discussing and trading tips on how to rape and abuse the women in their lives, and most recently a horrifying revelatory investigation into Czech child pornography rings on Discord (this article comes with a firm content warning). It was written against the emergent fascist controls to freedom of speech regarding queer and trans identities on Facebook and Instagram, and against the performative blockading and re-release of TikTok in the US. It comes against Trump signing, on his first day back in the White House, a punitive order against trans and non-binary identities.

If there was ever an impression that equality for women, and acceptance and normalisation of queer and trans people, was on the way — or even arrived already — in the West, the last few years has seen its destruction. The febrile equilibrium of acceptance or tolerance of queer people have enjoyed, in some places, teeters wildly. A grim forecast, but a simple truth remains that in most places it is the older generations pushing the intolerant agendas. There’s a million metaphors involving the coming of dawn, for good reason.

For the last of my political review articles for Easterndaze, I investigated three emergent events in the Czech underground club scene which cater to queerer tastes, both in music and in other ways. There are’s many that I’ve missed: Dick is the first port of call for the gay techno and house scene, while events like Whiskas signal queerness with maximum sound, blood-bursting BPMs, and its visual aesthetic. Other events not covered also address gender diversity, such as Fuchs2’s all-women FEMXCORE series, or showcase queer acts in subtler, softer settings, such as Aqueerius at Ankali. The list continues, and new groups emerge frequently.

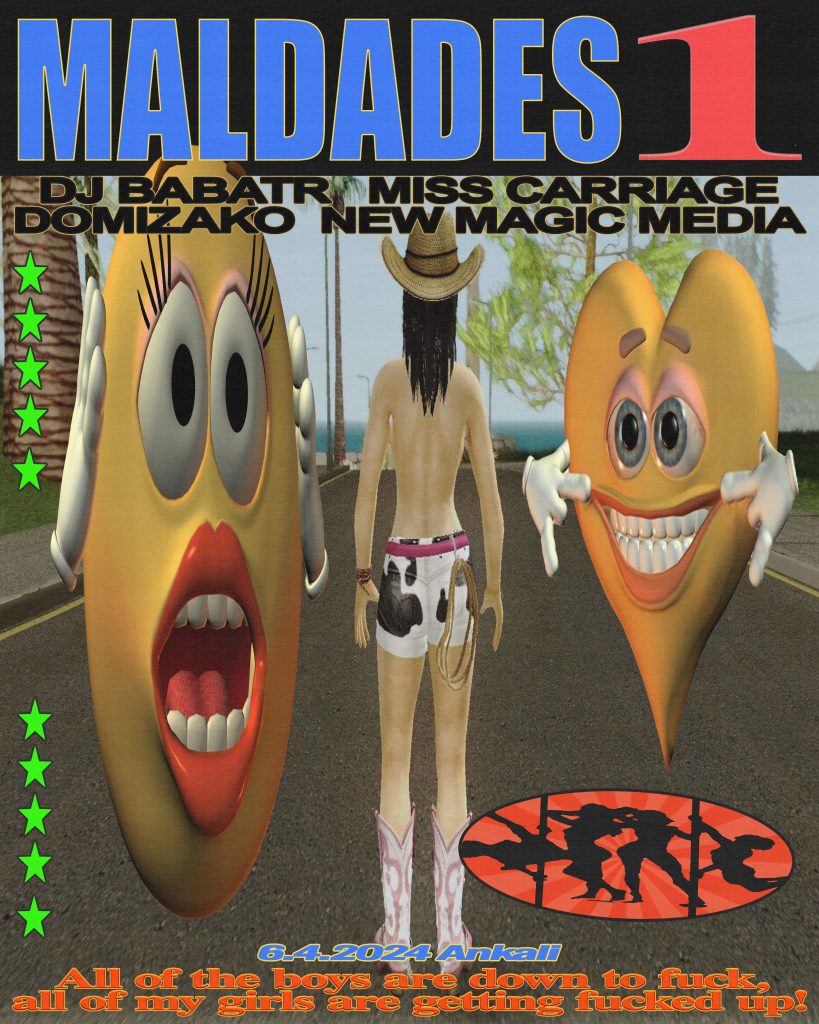

One recent addition to Prague’s queer clubbing scene, Maldades, distinguishes itself by shirking techno, instead stitching contemporary Latin club music and hyperactive pop edits together in cheesy nitroglycerine magnificence. The party’s Chief of Operations, Miss Carriage (real name Matyáš), cuts a confident and outspoken figure on the scene, backed by his wild selections and boisterous mixing technique to compliment. Breathless reviews have flooded in for his sets, especially his recent back-to-back closing set with Slovak star Domizako at Ankali’s New Year’s party, and he’s astute with selecting artists for Maldades who fetch similar praise.

Maldades follows the template of a lot of nights here, with a sole foreign headliner — Bitter Babe, DJ Babatr and DJ Florentino have graced the decks so far — while the rest of the night’s sets are made up by local people. In Maldades’ case, that’s always queer people, or the staunchest of allies, all punching out thumping bass, kinda stupid but very dance-worthy edits; generally vibrant, fun, dance music. Maldades is absolutely a gay night out, being curated by a gay person to provide an event for “queers & allies”, but any overt labelling stops there. The posters aren’t plastered with chains and black leather, but with irreverent and unserious designs — “come with a similar attitude”, it says without words.

Poster: Petr Menhart / @penetraheart & Kristyna Kulikova @krstnklkv

Matyáš’ ideas of promoting his club night can get Ankali in a bit of trouble with the stiffs at Meta, but it’s hard to imagine it any other way (especially with the current stifling of queer and trans content on Meta’s websites). For December’s Maldades, all the stops were pulled out to give the club the right aesthetic; sleazy neon signage, weathered lounge furniture, and a stripper pole were installed on Ankali’s main floor, giving the feel of a backwater casino. To promote the night, the club set up a small photoshoot with Matyáš reading out homophobic comments from Instagram while drinking Prosecco in a hot tub. He seemed a good person to get a quick and honest image of what it’s like living openly gay in Czechia, from the perspective of a Czech local, and also a view of his experiences with the club scene here:

Can you describe what it’s like growing up gay in Czechia? How well tolerated is it?

I think that the experience differs a lot based on where you come from and how “queer presenting“ you are. I come from a rural area, and it was never very hard to tell that I’m gay – so I was pretty intensely bullied for a long time. This experience definitely shaped me in bad ways, but in good ones too – I am a very funny person and it is not easy to catch me off-guard, but I will also be unlearning living in constant fight-or-flight for the rest of my life.

How does the nightlife scene differ [from “everyday” society]? How is it similar?

I think that the “alternative“ nightlife scene in Prague differs in the extent and the ways of discrimination. Nobody will openly call me a fxg or beat me up of course, but I have experienced a pretty high number of microaggressions.

What are the major obstacles for acceptance of gay life in the nightlife scene?

I think that the issue is that people “accept“ queer people in theory. They have this sterilized idea of us as “normal“ people just like anyone else, who just maybe like to have sex with men instead of women. And they cement this idea by accepting the small percentage of queer people who are really like this into their circles. But most of us aren’t different just in our sexual preference or gender identity; we have very different values, tastes, hobbies, ways of life and speech – all based on our very different experiences, trauma, social status, and brain organization.

Are there some positive areas?

I think that the positive thing is actually feeling the (very) gradual change for the better and actually being part of the change — just by existing shamelessly, or with my club night Maldades. Also seeing new much needed collectives like the trans-femme ESTROGUN pop up and be successful.

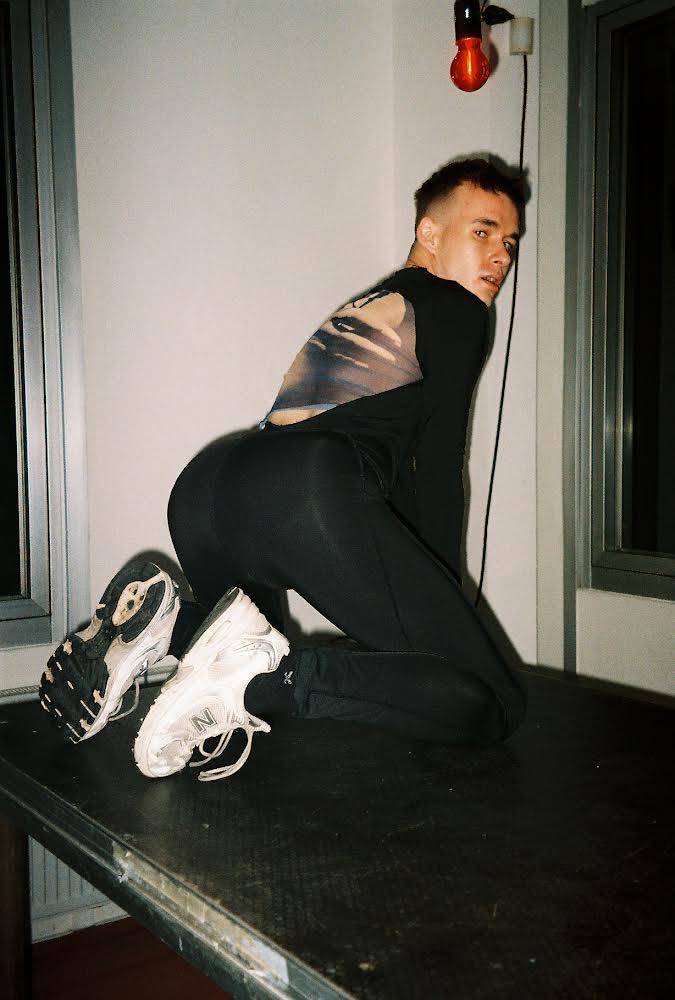

Photo: Maldades (Rita Baby)

My first experience of Prague was at Lunchmeat Festival, and one of my initial impressions was of how integrated the queer individuals in the scene seemed to be with the rest of the city’s nightlife community. This was something of a misdirection, a combination of reasons that include the wide appeal of the festival and the fact that SOPHIE was booked for the final performance of the festival (so, duh). It dawned on me after moving to the city that the established and predominantly cishet-operated club venues and off-location events set the paradigm for the kinds of cultural events in the city, and what seemed like integration was largely a result of the city’s smaller size in comparison to London. The thought then developed that there maybe weren’t enough active clubbers in the city to fill a room exclusively with queer people, and instead the two groups shared space in the crowd as a result. That realisation eventually faded in turn; greater knowledge results in a greater understanding of one’s ignorance.

As I see it now, there has long been a complicated relationship between the straight and queer people in Prague’s nightlife, something that asks for words like “necessary tolerance” instead of “enthusiastic solidarity” — often a two-way street. That picture is certainly changing, Maldades being a part of that change, and I’ve tried to paint something of the bigger movements in the previous articles I’ve published through Easterndaze, on the trans-femme collective ESTROGUN and in the groups covered in the recent piece about racial diversity. As queer people become increasingly central to the organising groups in the nightlife, rather than being more confined to the crowd, progressive safeguarding changes are being made, as standard, that are not guaranteed in many of the so-called Gay Capitals of Europe.

While the chief underground nightclubs here are displaying increased awareness of the necessary protections which queer people may require, there are also what might be crudely called oversights, and with grim results: the creation of “safer” spaces has been a hot topic in club public discourse throughout my four years living here, yet sexual abuse is still perpetuated in the clubs. GHB (a drug taken frequently within the gay community) has claimed a high number of young lives in the four years I’ve lived here despite the substance being openly outlawed at many parties and clubs, due to its risks. There are periods of quite open public discourse about the substance and the harm it can cause, but as with most permissive and accepting drug education, the punch fails to land with the gravity the topic demands when there’s no obvious consequence — until it’s too late, again.

These are of course daunting challenges to even the biggest of nightclubs, and every venue, from Berghain to Fabric, must deal with sickness and death due to overdoses, or with sexual harassment complaints; whatever Prague lacks in providing safety for its clubbers, every city is lacking also. But, despite the history of both the clubs named above, I see more being done in Prague’s venues in the way of drug education and other forms of safeguarding. Being a small city has some benefits in this regard; there’s a much higher percentage chance that you’ll be at a party with a harm reduction station or trained awareness team, because the underground clubs here tend to share heightened standards sooner or later.

As the nightlife scene in Prague comes into its own as a commercially viable “industry” more alike to other capital cities, events marketed as “sex-positive” and/or queer” have been on the rise. Some of the events have few or none of the additional necessary measures these events require, but many follow the way set by queer nightlife pathfinders like Pu$$y Palace, Lecken, or Temporary Pleasure when setting up the way the event will run. Most events of all natures are making both spoken and unspoken steps to bring more diversity to lineups, but while the labels of “queer” and “sex-positive” may indicate enthusiastic support, it may be surface level, without the years of experience needed to produce an event authentic to those high standards.

Photo: Liliana Drekaj / Cunt

My informants for the article about racial diversity in Prague have faced backlash when setting up events “only for a specific group of people” (translation: specifically catering to a group ordinarily marginalised, but welcoming all). Those creating events aimed at gay and queer people, or for women and trans*/non-binary people also receive backlash, sometimes “publicly” on social media, other times face to face, and at others behind backs. There’s not a better example of this than with the recently-launched night at Ankali, Cunt, a femme-forward event run by Ankali’s bar queen Ksenia along with nightowl and photographer Liliana.

The first of its kind in the city, Cunt is a kind of soft-play party intentionally for women — less than a full-blown whips’n’chains sex party, more than an average clubnight. Ahead of the first night, the pair hashed out what Cunt’s all about for the Ankali blog, and I recommend going there to understand the night’s ethos in the girls’ own words. Within, they explained the door policy: all who have “a connection to femininity and womanhood” are welcomed to Cunt, or must be vouched-for at the gate by a woman, to secure it as a women’s play party.

The wounding of masculine pride when confronted with an adverse door policy is sadly a worldwide phenomenon, but what startled me most about the angry hum over this was the entrance policy seemed to me to be an incredibly open door. With Ksenia and Liliana now readying their third event, I sat down with the pair to hear how things have been going:

F: Perhaps it would be best to start with what Cunt is about for you: what its values are, how you ensure your event is safer for your audience?

K: I think the main thing is we really, really, really try to make it comfortable for people to feel safe enough to explore. It’s not mandatory for you to do something sexual, but you do have space for it, and you do have safe space for it. There is not gonna be someone staring at you, interrupting your play, or something like that.

F: And you have people in the dark room, making sure that doesn’t happen?

K: Yes, they are people who’ve been doing it for years, they’re doing these sessions separately, and you know you can trust them, that they know how to do it safely. This is our goal: to have people who know how to do things safely — being practiced with wax, etcetera — and you can try it out with them. Then you can see if you want to take it to your bedroom or not, if it’s something that you feel like you want to explore more and get into it, or if it’s enough for you to just try it out at a party. We want to be something in between going to hardcore BDSM parties, and just a party. You can dance, you can explore, but nothing of this is mandatory.

F: So, instead of just leaving a bunch of whips in a room, you’ve got someone there that’s actually experienced with impact play?

L: Yeah, but also, away from parties, we’re really trying to focus on educating people about what we do, the things within our party. We are starting our residency with Shella [Radio] where we’ll do talks about different topics, anything related to sex, anything related to women. And then we also do Cunt talks in Pluto [Ankali’s listening room], where we had our shibari artists come and give a workshop on it, where you can come with your partner and buy ropes. Another thing that is really important to us is listening to feedback from people, and trying to apply it. People know who we are, especially after our interview with the [Ankali] blog, so throughout the night, people also come up to us, talk to us, send us messages. And we try to listen and change anything that people are not feeling. At our last event we maybe had too many men because of Halloween, so now we’re sitting and discussing how we can make the door policy better.

L: We absolutely do not want to write on our posters “no men”, because at that point, you’re giving them a place to say stupid shit. Some of our closest friends just can’t comprehend why we need a space, and then you’ll hear these stories from women that just feel utterly uncomfortable at parties. So many women came to our party completely alone; I have never felt this way in any other event, even me. I’ve been going to the clubs for like four and a half years, I know the people running the clubs, and even then I feel uncomfortable going alone. So, to be able to have a space where you can do that — where you can see people you know, that you know you can trust, and know that you are taken care of throughout the entire night — a lot of places just don’t serve that. I think that they’re trying to better themselves, but it is gonna take quite a while and a lot of community effort to start making club spaces safer for women and anyone that feels a different connection that’s not “masculine”, or being tied to “being a man”.

K: At the last event we noticed quite a few women bringing their guy friends, that are just friends. I understand that you feel that your friend is safe towards you, but you cannot know how other people — that really need the safe space — will feel about them there. We are open to letting people come with their partners, because they want to explore and they want to experiment in a safe place, but it’s not a space where you can just drag your friends in because you wanna hang out. You need to be really mindful of people around you. And I think even if our target crowd, let’s say, think that they should bring their friends and that’s appropriate, really shows that we need to talk about it more and explain why this event functions the way it does and why we wanted to be the way it is. After the last event, a few people talked to us about not feeling as safe as at the first one because there were more men. We noticed too. It might be because it was Halloween, and people just wanted to go out that night and whatever, and they felt like that’s the right space to go.

F: I just want to ask about that — because I read the blog with Ankali where you said that you’ve gotta have this “connection to femininity” to get past the door — and a lot of the people that I was speaking with about the event would say something like “I don’t really understand why they’re trying to keep men away”, but now you’re saying that there were too many at the door?

L: I mean, we even had an instance at this Halloween party where a group of men came to the party and said that they were there just to watch women play.

K: And the fact that they would just say it on the door, to the door staff?! Obviously they were not let in, but the fact that they came with the idea that it’s a place for them to check girls out, and the confidence to say this to the door person as well?!

L: At the Halloween event, we played different games within our event like spin the bottle or truth or dare, and men can’t partake in these games. The point is that it’s for women, and the men can’t play. So, you’re gonna sit there and you’re gonna watch, and it’s gonna make people uncomfortable. Why would you want to be there? You are putting people in a position of feeling uncomfortable. We have a lot of people around us that do understand this, but I think that for some, it’s just immediately like, “you are isolating an entire group of people.” But, take Dick, for instance: this [party] is labeled for queer people, but it’s really for gay men. So, these groups have a space, and the only people that don’t really are women. Earlier you asked about this “connection to femininity”, but it’s not just about a connection to femininity, it’s whatever you feel, in any aspect of what is related to your vision of being a woman. This is completely on you and how you feel. We don’t police this whatsoever. We’ve had some trans people asking if this is a trans safe party, and I think maybe we do need to talk about it more, the fact that we are. For us, this just comes naturally; we don’t have to say that “trans women are women”, because for us it’s a given. You always have a space with us. This is a safe space for anyone that is coming. But, we ask you to be mindful. Is this a space that you need to be at? Is this a space that you are searching for? Because if it is, then we’re here for you, but if it’s not something that you are needing, then we ask you to be mindful of the people that do need it.

K: If you just want to be involved in something that seems secretive or special, that’s not the reason to come to Cunt.

F: Do you feel like you kind of got more work to do? You’ve drawn a little line around yourself, and you say, “we’re not a “not-man” party, but we’re building a special place for people who are not being catered to”, and now the pressure to be perfect seems so much higher for you, and people doing anything similar.

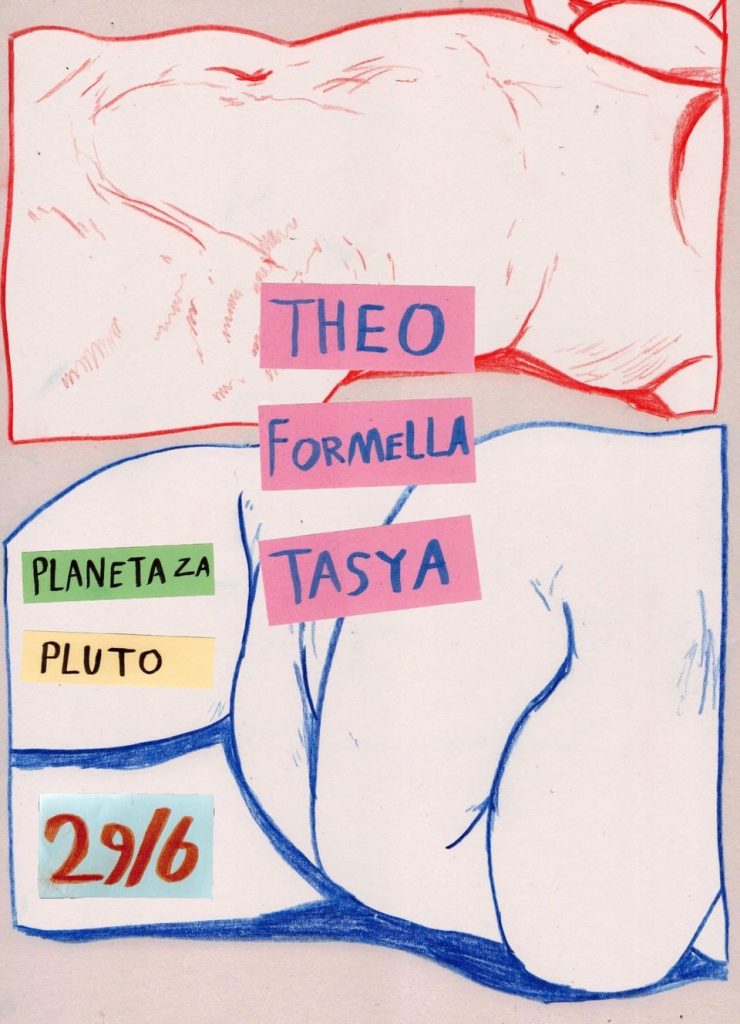

L: I think it is like that. People are really trying to force us into a box. I can’t speak for Ksenia, but for me, I’m not a person that believes in labels. I don’t need to believe in labels to feel heard or seen, and so I immediately think about that for other people. We are constantly trying to do better. If we have ever done something that has made people feel isolated, we reflect. Any time that we see a comment, any time that people message us, we sit down, we talk about it, we figure out what we’re gonna do and how we’re gonna make it better in the future. I think that a lot of parties maybe don’t take this into consideration, feedback. I think that having a space like this is so important. We have a new resident, Tasya, and Tasya is nonbinary, but they have also once had a connection, and have felt what it is like to be a woman. I think that it’s important that no matter who you are, what you are, or what you identify with, you do have a space. But it’s hard, you know.

F: It feels like a lot of the other parties can just drop in, and pick and choose, and be like “hey, we’re doing a little bit more female diversity on the lineup”, or “we’re adding a little bit of transness to it”, or something like that, but they don’t talk about what that means, and it’s not really solid representation. But then, the people like you who are actually trying to draw a line around something — with a fuzzy pen — and say, “actually, this needs to be treated in a slightly different way”, these people don’t get the same freedom of behaviour.

L: This was actually a big thing that we faced when we first did our event; we’re trying to start something new, we’re trying to go out of the box, we don’t wanna label things, and we had so many people come up to us and say, “you just need to write on your poster that it’s a FLINTA event”. For us, we haven’t gotten to this point yet, we don’t know how the space functions, we don’t know what crowd it is. It’s very niche, you know? It takes time.

K: We are not in a position to define what is a safe place for trans people. We cannot, we’re not trans. We will try, of course, in our power, to make the space feel as safe as possible, but we didn’t have those experiences, to be able to say that we are a safe event for trans folks. We’re so open, but we can’t [say that]. We can be in a position to decide what’s safe and not safe for women, because we are women. We can be in a position to decide how to make the place safer for us. This is why we try not to label ourselves in this way, because it will be very… unfair, I believe…

Photo: Liliana Drekaj / Cunt

I spoke to Ksenia and Liliana a day or so after they came back from Brno, Czechia’s second city. They’d been to Bent, a “sweaty fuckfest” night run by the people behind the Vitamin nightclub. A country’s capital city can often steal the thunder from the smaller city’s scenes, but in Brno there are groups and artists bottling up homebrewed lightning to rival Prague’s own. Illustrated with slick, gooey art by house photographer and visual artist Paulina Masevnina, Bent is, at least to my inexperienced eyes, a forerunner in Europe’s queer darkroom scene. The event speaks with a unique tone, equal part naked desire for hedonistic fucking, and frank, bullshit-averse honesty.

Over the pandemic years, darkroom parties in London and the UK seemed to be coming out of the walls, the flooding promise of the UK’s second ‘Summer of Love’, with thousands of untouched bodies aching for pleasure; unlike the first time around, though, active steps were made for social-group engineering, with parties taking painstaking measures to ensure the crowd would get along, adhering to a dress code of fetishwear and leather (“no jeans and T-shirts”), as well as align against a list of (misdiagnosed, I argue) “phobias”, from homophobia to transphobia to fatphobia. The marketing and design for these events was sleek, with photobooth areas ushering in a new phase in post-COVID culture, and although one-sheet manifestos and party laws were already pretty commonplace — not least at the mostly hushed-up sex party events that already existed — they became ubiquitous and essential henceforth, even at what might be called fairly “typical” club events.

Bent does draw similar lines to these parties, but reflects the context of clubbing in Brno versus places like Hackney; At Bent the admittance criteria is less circumspect, but the door shuts hard on any meddling with the party’s good time. They stipulate what kind of outfits are appreciated, but when stripping to your skin on the dancefloor is an option, who really cares how you arrive? “What’s even more important is not to make a caricature out of yourself just because you really want to get into a party” they wrote via Telegram ahead of the recent party, “that’s not sexy.”

It’s clear they’re trying to dissuade any posers: Bent smells of sweat, and whatever other human fluids, by intentional design. If the constraints of Cunt (or other events) irked you, then Bent is the event to check. It’s still far more safe than your average dive bar free-for-all — there is a check and questions at the gate, a dress code, a blacklist, a trained awareness team — and yet Bent does feel quite close to total mayhem. It plays, as with most similar parties, with a delicate balance of unbridled hedonism and subtle-but-firm safeguards to try to encourage a radical exploration of the self and its limits, to summarise the words of Servicebot in his piece for Bent’s blog.

Cunt’s Ksenia and Liliana went south to check how the party was run, with a good chance that they’ll be helping with security for the night. From the short chat I had, it’s clear that some things get by at Bent that wouldn’t fly at Cunt — for one, Ksenia is adamant that a dress code is essential to protect the night from creepy tag-alongs, and we fly into a discussion over this.

Cunt, poster by: @withapencilinhand

Alongside the political developments this article began with, any contemporary discussion of the rights of Queer people in Eastern or Central Europe has to include the worrying developments of the political situation in Georgia. Gábor Erhlich’s writings for Easterndaze paint the background of a political flashpoint which flared again at the close of 2024: the inciting act from the government, passed in May 2024, is what Georgian LGBTQ+ rights groups are calling the “Russian law”, relating it directly to Putin’s crackdown on queer identities due to the explicit prohibition of what Moscow (and now the US) calls ‘LGBT Propaganda’. This law coincides with retractions of Georgia’s bids for EU membership, a sharp burn for Georgian youth in particular who ally themselves with “European values”, and against Russian influence.

For a brief window my feed showed videos from Georgia including a woman tying her hair up under water cannon blast, a man aiming a firework Gatling gun at police, and innumerable videos of a seething mass of young and masked demonstrators battling — and I do mean battling — against armoured cops. Georgia’s underground music scene has, quite rightly, gained some infamy over the last decade due to the extensive involvement of the local club community and nightlife venues like Bassiani, TES, Khidi and Left Bank, amongst others, in organising raves as political activism against the acting government. For many years now there’ve been powerful images and strong words coming from organisers in the territory.

During the recent uprising, messages published by the Georgian nightlife community gave unified instructions to resistance groups; individuals shared tear gas remedies, hotspots to avoid, and cinchpoints to join. They shared images of rubber bullet wounds, evidence of police brutality, and the distribution of mutual aid. The club community seemed out in force, and ready for the fight. The public eye shifted, but not before Georgia, once again, left an impression of its willingness to engage physically with its political causes, and in doing so sent out lasting messages to allied scenes. In Serbia, some nightclubs have joined the massive student-led protests against government corruption.

Prague has a music scene generally quite enamoured with iconoclasm and challenges to the state, tempered in the individually unique political climates that are shared amongst ex-USSR territories. Resistance against Russian imperialism, and the fear of it, is an instinct shared by many of the younger people here, but in Georgia, “Rave as Resistance” is not a conceptual line drawn chiefly around self-liberty, self-actualisation, and probably drug consumption, but rather a political reality demanding participation at risk of erasure. The raincloud of public discontent in Georgia has grown full and burst, with very real implications, and I wonder what it would take for the scene here to take to the streets in balaclavas, armed with fireworks and petrol bombs.

Prague’s own cloud of malcontent with the deepening Right might be growing darker and heavier — especially with Slovakia’s recidivist government darkening the doorstep with their crowing of the selfsame Russian lines about “gay propaganda” — but I have my doubts that the instigating unifier for a Czech people’s revolution would be anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. I hope I’m wrong, and that we won’t even get to that point, but the voice saying “be prepared” hasn’t gotten any quieter lately.

Text: Freddie Hudson

Lead photo: Liliana Drekaj / Cunt

This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.