Where Sound Finds a Home: Lviv’s Home of Sound and Its Many Faces

Published May, 2025

by Olena Pohonchenkova

How post-2022 Lviv is finding new sounds and ways of expressing them through the tape archive-cum-sound laboratory.

The Theremin Auto website is designed as a tube made of thousands of grey effects units. It feels a bit claustrophobic but also womb-like safe, in the main menu at least. I’m choosing a song called Horse in Ancient Rome, and my in-game hand gets to fly forward, catching the blue units that produce the sounds for the song while avoiding the electric fields and exploding blurbs that, for reasons unbeknownst, levitate in the tube alongside my hand. The touchpad barely responds, and my result is “all fingers cut off” in less than a minute.

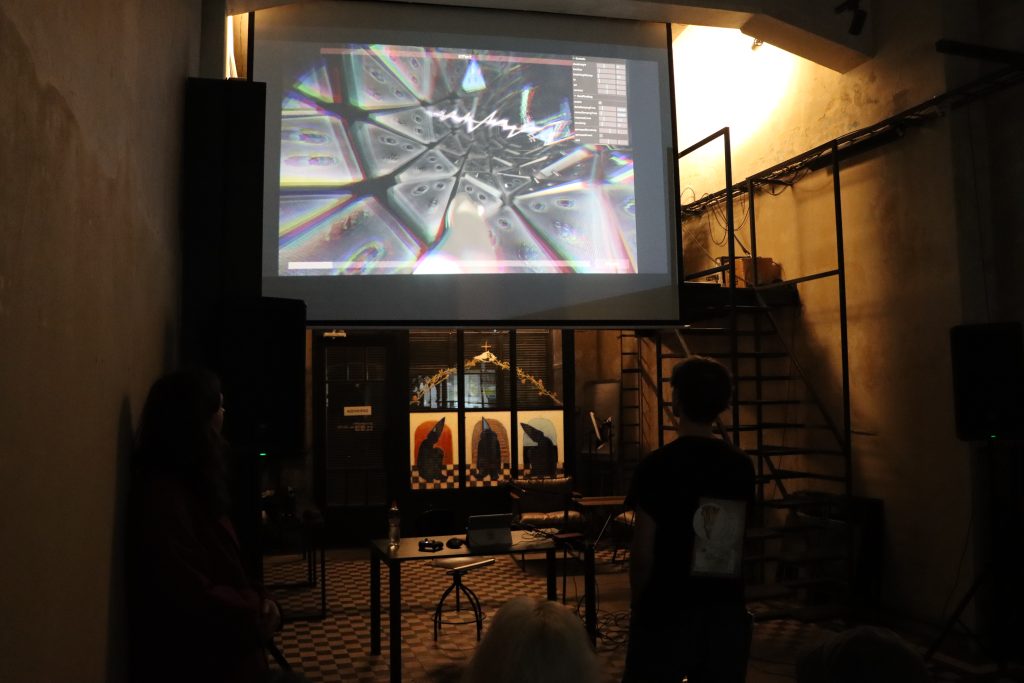

Theremin Audio presentation, photo: Oksana Demych

The game’s name is a nod to the theremin music instrument and its inventor, Lev Theremin. Just like a theremin, it’s supposed to be played without touching, and that’s exactly how it was played at Home of Sound game presentation this April. The creator of the Theremin Auto goes by the moniker Shaded Gallery and is a member of the radical sound formation, a community of artists and musicians that formed in Lviv in 2023 but which has no Lviv-born members: all of them moved west from eastern and central parts of Ukraine in a post-full-scale Russian invasion exodus. Shaded Gallery’s other creations include a mushroom drums emulator, a 3D ‘live recording’ of a Ukrainian experimental musician, Sasha Dolgiy, playing a magnetic bandura, and an imaginary gallery with clay figures by another radical sound member, Hanna Hak.

radical sound has been playing small venues all over Lviv for about a year before contacting Home of Sound with a collaboration offer. “Since everyone in the formation has day jobs, we had to meet here during my non-working hours”, smiles Pavlo Koriaga, a Home of Sound [Home of Sound is a part of bigger cultural institution called LME ‘Lviv radio’. LME ‘Lviv radio’ is a Network (Merezha) for Cultures and Technologies. It is a platform that unites the experiences of art, culture, technology and science for a better quality of the future.] project manager who closed the deal on the unlikely collaboration. The gap between ‘working hours’ (for Home of Sound workers) and ‘hobby hours’ (for radical sound artists), sound research, and circuit-bending enthusiasm is the focal point in a dialogue between a state institution and a grassroots initiative. It resulted in a three-part collaboration with live shows by ЧОМУ? (Ukrainian for ‘why?’), anton malynovskiy and Буду Думати (Ukrainian for ‘I will think’) with Hanna Hak.

Bohdana Tkachuk, the lead manager at Home of Sound, was particularly impressed with anton malynovskiy’s performance, which was her first time experiencing a noise event. “They took this cassette with the pre-election speech from somewhere around 2010, where some deputy is campaigning, manipulated the recording until it’s drowned in the noise, but at the end, the voice reappeared… And at this point, you’ve got to perceive it differently.”

“I’m used to listening to harmonies in music: you might like them or not, you might feel the rhythm, dance to it… If it’s an opera, for example, you know how to act. Here, the experience is completely different because the sounds awaken various emotions in you; it’s a kind of dialogue between your inner space and the author of the noises you perceive. I was still looking for a deputy’s voice when it drowned.”

“I took a really funny record from Home of Sound archives: a politician, Oleh Riabokon, addressed his audience before the 2010 elections. It was so meaningless that it could easily fit any other Ukrainian elections, so I used lots of delay and made it the core of my sound performance”, shares the artist.

anton malynovskyi preformance. Photo: Daria Kniazeva

“anton ended their performance with their own impression of how all pre-election campaign speeches sound the same, eventually becoming noise. The record ended with “we will win!” and it felt so relatable to what we’re experiencing at the moment: the war noise, the information noise, and still, the expectation of a bright future”, Bohdana continues. “radical sound are innovative at both understanding contemporary art and representing it. They capture today’s social and political problems”.

For their show, Буду Думати & Hanna Hak reimagined an old folk tale from Dnieper Ukraine called “The Funeral” with the help of clay and DIY music instruments. Clay was used as a working area, a material for hand-building figures in real-time stop motion animation, and as a provider of sound samples for the music part of the performance.

“We recorded all these clay sounds at home: the hiss, the fractures, and then they accompanied the performance”, shared Volodymyr Milchenko aka Буду Думати after the event. “I hit it, kneaded it, threw it in the water, it had the small dry particles inside, which made the sound so colorful”, clay artist Hanna Hak adds, “clay has a lot of sound in itself, and it changes depending on the substance it contacts, like water, fire or anything else really”.

“At first, we also wanted the claywork sounds to be live, but didn’t have the equipment for that. Still, we tried to keep the interactivity in the performance, so I also bought several piezoelements that can capture sounds, organized them into 4 channels, and connected them to my mixer. I also used the noisebox I made”, the musician comments.

However, manipulation of pre-recorded sounds worked great: while Milchenko solemnly recited the tale about a rich man who arranged for his dog to be buried like a Christian, layering the recital with noises, Hak organized scenes from a tale on a clay board, permanently reconfiguring the patterns, kneading them back into a pile of clay only to give it new forms. The whole process was projected onto a huge screen that faced the audience. Hak’s pace was different from Milchenko’s soundwork, bringing a counterpoint to the performance. “I suppose this tale is about the preciousness of memory: how one can knead it, transform it, damage it, and how we should try and keep it”, she shared after the event.

The first radical sound concert was also the one most radically sounding: Kharkiv-born and formed duo of Daryna Berdynskykh and Ruslan Kod called ЧОМУ? doesn’t court long buildups, instead coming at the audience with the wall-of-noise sonic tsunami. For the next hour, you’re free to roam the turbulence of it all, picking the fragments of original sounds that got twisted and distorted in the process. Their live show was accompanied by visual art from a frequent collaborator Vlad Tretyak: in it, videos from Berdynskykh and Kod’s archive were processed in real-time, slowly getting out of their humdrum shell and becoming a part of the noise canvas.

“Our regular audience was a little bit puzzled”, remembers Pavlo. “They kept asking what that was. The show was loud, and it was happening in our basement. We left the light at the entrance, but the ground floor area (where most of the events take place — ed.) was dark, so we were literally luring people there. Some left, but still, they made an effort and came to see something new.”

Although it was expected of the Home of Sound to exclusively provide the institutional space for the live performances, the managing team agreed to let Berdynskykh and Kod into their tape vaults. “We showed them our archives, and they seemed interested in turning archival recordings into sounds. So we agreed that they would take some of the archival recordings, transform them, and present the results during their show”.

***

When faced with a question about similar institutions abroad, Pavlo and Bohdana hesitate: “Well, there are archives… but, strictly speaking, we’re not one of them”. The Home of Sound is a kind of institution that could only appear in this place and time: in a country at war with an imperialistic neighbor, yet in a town far enough from the frontline to engage in cultural life. Residing in a neo-Gothic building from 1912, it used to be the place for Lviv radio, first in pre-war Poland, then during Soviet rule in Ukraine, and then throughout its independence until the teleradio company closed the station and left in 2015. Polish, Ukrainian and Russian history interlace in the archive of tapes left from the radio days: scars and phantom pains of the tumultuous 20th century run through them, while the fractured memory of the past keeps the team of archivists, sound researchers and cultural workers alert for the ever shifting reflections and politics of today, both in the realm of sound and beyond it.

Archive tour. Photo: Oksana Demych

“The tapes were a dusty mess when we got here. During all the reshapes and reforms, since 2015, the archive has been moved many times, and some tapes were lost for good”, says Pavlo. “Now we’re focusing on making its conditions safe and effective: we’ve just rearranged all the tapes in a new room and are looking for ways to build the air circulation system and other necessary conditions to keep the tapes from falling apart”. The earliest tapes in the collection come from the 1950s, and its bigger part is deeply connected with Soviet history.

“The Russian part should be kept for the decolonization research, but also we’d like to show everyone how many Ukrainian materials are kept here. These tapes are unique, you would never find them on the Internet: recordings of factory and plant workers’ ensembles, concerts in houses of culture, things that are unknown or forgotten. The whole grassroots music culture of Lviv, but not just Lviv: people sent tapes from other cities, and made copies of records. Now we’re working on digitizing and keeping it, not just sitting on it, like a dragon on a pile of gold.”

The tapes were arranged just recently, but the room where they are kept feels like the heart of the building. Being here, you start to get the concept of the space and the ways for it to work. There are about 18 hundred tapes overall, and the big work of digitizing them will start this spring. Bohdana and Pavlo take me to the 4th floor and the soon-to-be digitization studio — a light room with a high ceiling and windows that face old Lviv’s rooftops. It has newly painted white walls and two tables that smell of cut wood.

“We have a concept of this whole floor as a laboratory, where anyone would be able to digitize their tapes. One of these days, the necessary equipment will arrive”, says Bohdana. At the laboratory, Home of Sound guests, whether artists or researchers, will get an opportunity to work with the sound archive on the spot. Research, archival studies, and artistic work are deeply connected in Home of Sound. Pavlo shares the plans for tape workshops that will also take place in the laboratory space: in order not to involve the actual artifacts, the team buys empty tape and makes copies.

Earlier this year, the Home of Sound team did an open call for people to bring their old sound equipment that would be used in the laboratory spaces. Besides, it will have a small studio for making demos. “You’ll be able to bring your own instrument, and we’ll provide a sound card to make a recording. The room will be soundproofed. At the moment, we have several samplers, an electric organ, and a couple of turntables for kids, now the setup looks like a music Tetris, but we’re searching for ways to expand it”.

Different types of events are interconnected within the Home of Sound spaces. 2024 was a big year for sound research both within the archive and beyond it. (Non-)Lost Tapes lectures and listening parties series started as an archival work for a few tapes, but have grown into a large-scale research of different local musical strata. “It helped us realize what and when happened in Lviv, and learn closely the history of this building, the building of Lviv Radio from the 1930s, talk to the people who’ve been working or recording their music here”, shares Pavlo.

Reactualization of the layering of musics of the past lets the new light in on the crossing paths of different music communities of today. “Now we’re trying to organize the work of Home of Sound as a place of memory, but also looking for artistic collaborations and ways of re-actualizing the radio heritage”. The managing team agrees that you cannot work with memory in a closed space. As soon as you let the air in, in many ways, it becomes the thing of the present. And in the present, in post-2022 Ukraine, Lviv has become a sanctuary, a transportation hub, and a city where new ways of community-building are being tested.

At the entrance to Home of Sound, one can see the stained glass windows with shells, crosses, and watery colors. Those were painted by Odesa-born artist Dasha Chechushkova for last year’s project As for now, it is quiet. In dreamy, medieval-like depictions of impossible beasts, Chechushkova reflects on the neo-gothic architecture of the building as ‘church-like’ and invokes the early Christian depiction of churches as ships in the sea of uncertainty — a feeling very close to what she experienced when relocated to Lviv at the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

ЧОМУ_performance. Photo: Oksana Demych

The project focused on broadcasting soundscapes by Ukrainians in different regions of the country, as well as the places they went to because of the full-scale war, and lasted for three months. The stained glass paintings stayed as another trace of the new Lviv history that Home of Sound cultivates.

“I liked how the institution was always on our side: when getting the space ready, for example, there was no misunderstanding in this collaboration”, sums up Radical Sound member anton malynovskyi. “We’re going to continue to work with them, both on live performances and sound installations. It was also quite interesting that during these performances, non-musicians from our formation were introduced to the public, like Hanna Hak or Shaded Gallery”.

Open to various shapes and forms, Home of Sound is ready to do the hard work of building bridges and creating dialogues. “It goes perfectly with the concept of reinventing our spaces”, Bohdana agrees. “At the moment, with the opening of the laboratory of sound, we invite all kinds of experiments and experimenters. Lviv has its own underground, but it’s also something else, something completely different from an underground of this [new] kind.”

“On one hand, Lvivan audience is classy: the music Academy is right here, around the corner, we have Jazz Bez [festival], we’re sophisticated and all that. We’ve grown with a music taste. And then something strange, untypical, progressive appears, something non-Lvivan, and it takes root here very well”. At Home of Sound, the soil is formed for things to be rooted.

Text: Olena Pohonchenkova

Lead photo: Oksana Demych – The Improphase event with Ostap Manuliak

Note: Home of Sound is a part of bigger cultural institution called LME ‘Lviv radio’. LME ‘Lviv radio’ is a Network (Merezha) for Cultures and Technologies. It is a platform that unites the experiences of art, culture, technology and science for a better quality of the future.

Home of Sound is engaged in digitizing analog media and developing its own archival collection, while also taking care of the phonotheque of JSC “UA: PBC” (Joint Stock Company “Public Broadcasting Company of Ukraine”).

This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.