Jugoslavija Wave: New compilations revisiting the ex-Yu post-punk and new wave legacy

Published July, 2025

by Nikola Vitković

If I had a single ticket for the time machine that could take me to any historical or prehistoric period, I admit I would impulsively use it for the 1980s. And I’d certainly be in for a disappointment. A decade is a mere flicker if we want to explore what’s happened musically inside it. It’s a bit like trying to grasp what exactly happened during the Big Bang by witnessing it firsthand. We’ve been slowly unpacking the 80s post punk and new wave for the last 45 years, and there’s still much to uncover, so many stones to turn. In today’s ‘endless present’, we use the kaleidoscopic debris of the past to build our personal idealised version of it, and the liberal post-truth logic only smirks at the notion of objectivity. Who would bother to listen to any complaints on objectivity? If we don’t agree with someone’s particular reinterpretation of the past, we are free, just like Kurt Vonnegut’s tralfamadorians who exist outside time, to turn our head elsewhere and find other amusement.

Naturally, we have discovered and constructed those ideal versions of the past, non-objective as they may be, not only due to the temporal but also the spatial remoteness. In terms of music, it’s no wonder that often the best regional retrospective compilations are assembled in another country, like, for instance, my favourite 80s Yugoslav compilation, which was produced in Greece in the 90s. But the topic at hand is another compilation, assembled more recently in the U.S., under a plainly telling title ‘Jugoslavija Wave’. It’s a broad selection of [post]punk and new wave from 1980 to 1989 released during the Covid year on 90 minutes tape by World Gone Mad [a label with a sweet tooth for punk/wave heritage of the ex-Socialist regions, among other things] and freshly re-released this spring by Death Is Not The End label in the UK.

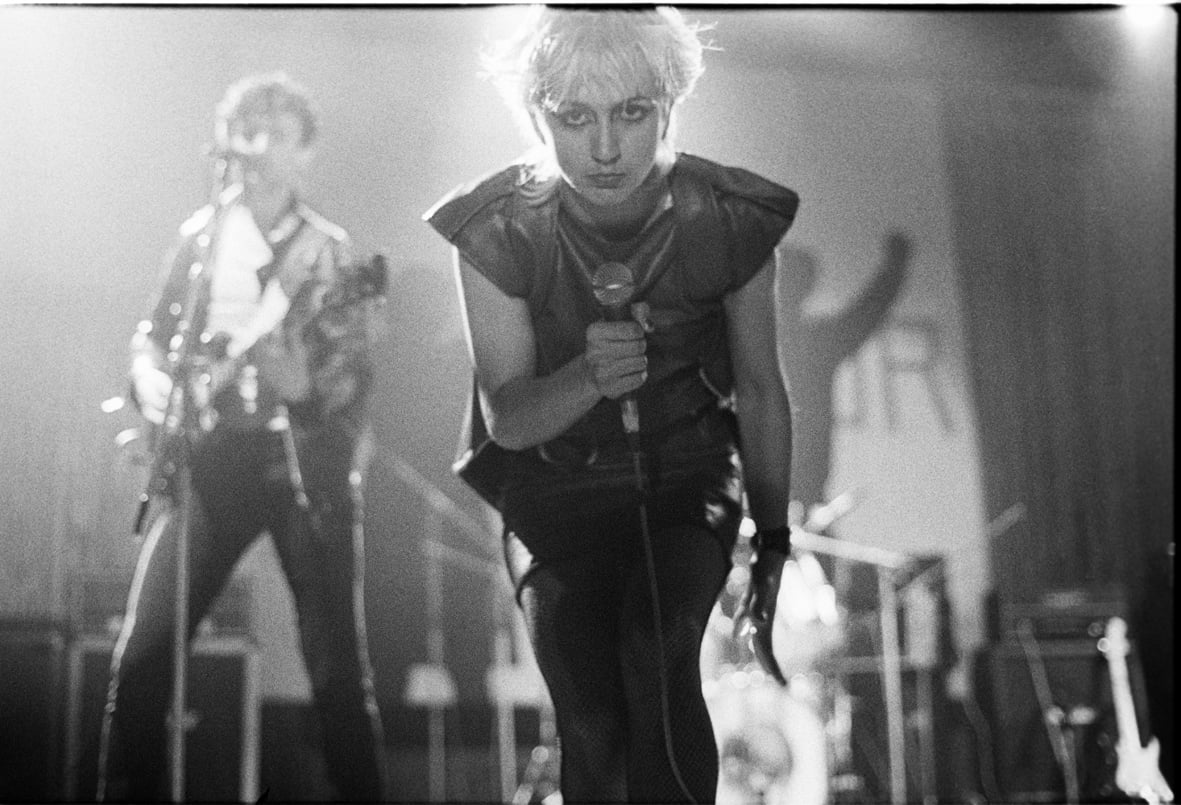

La Strada [photo by Slobodan Antić]

It’s hard to weave a firm compilation out of such diverse bands and styles as featured here. What holds this one together quite well is the thread of all things dark, ranging from not-too-extreme shapes of what goes today as post punk, to the edgier side of new wave. I could also describe it as a walk through galleries of Yugo underground’s higher floors, safely above its catacombs.

Fortunately, the selection doesn’t feel obliged to act as an encyclopedia and include the usual suspects. The absence of most bigwigs is a relief. Yet more kudos for avoiding the extravagantly obscure stuff – the comp refrains from snobby exclusiveness, treats the listener fairly, and just blasts a barrage of catchy tunes.

So what do we have here? Apart from an obligatory bare bones punk number [Električni orgazam, Azra], the tape is a showcase of post punk in its many forms: misantropic anthems [Paraf, Kaos], claustrophobic stroboscopic brainwashes [Disciplina kičme] savagery and gore galore [Grč] straithforward gothic rock [Phantasmagoria], angular, surrealistic vortexes [Let 3], then it leaps across the fence into the new wave yard [Jakarta], through the garden of synth pop, albeit subversive [Videosex] all the way to electronic body rock [Borghesia] and suspiciously far into martial industrial [Laibach].

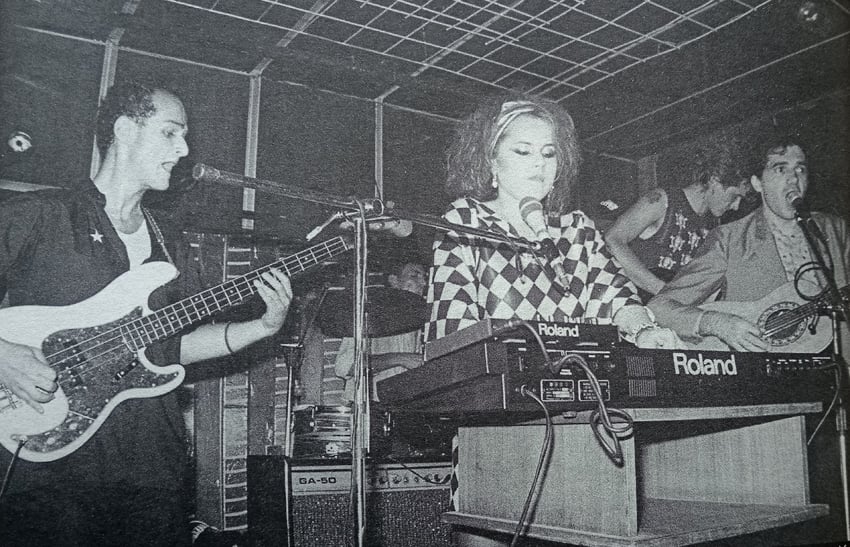

Grč [Grč archives, thanks to FOAD Records]

The tracklist inside the cover pinpoints each band on the map of Yugoslav republics, helping us construct the psychogeographical map of the federation. Though the republics are not as telling as the map of cities would be. And when it comes to post punk, the whole Yugoslavia was a suburb of the city of Rijeka – its electrifying atmosphere graces our ears from the first seconds of this tape with Kaos – Satovi bez kazaljke.

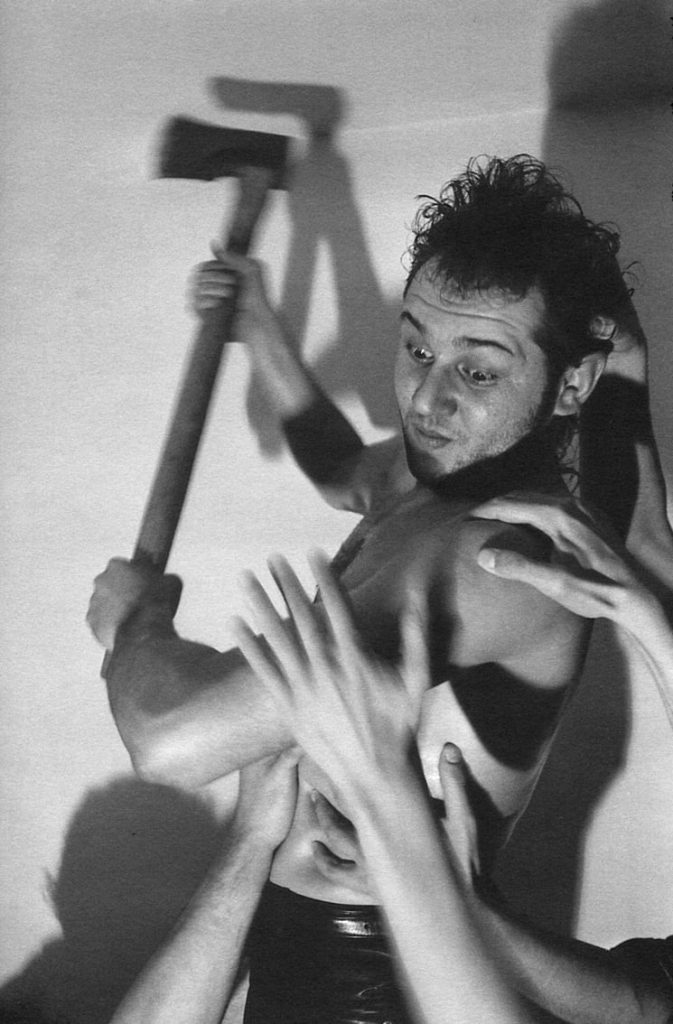

Growing up in 80s Belgrade, where all the bands were worryingly normal, I was always under the impression that the privilege of life in the capital of the federation comes at the price of restriction on craziness. Or maybe all those fancy pants were just a syndrome of conformity to the center. If I’d draw a map, I could put Bowie in place of Zagreb, Jimi Hendrix at best on Belgrade, Johnny Rotten on Rijeka, and John Koukouzeles on Skopje. The compilation presents 9 bands from Croatia, 6 from Slovenia, 12 from Serbia, 1 from Bosnia, and zero from Montenegro and Macedonia. Which brings us to the biggest flaw of this release: why on Earth doesn’t it include Macedonian acts? Macedonia had a striking and probably the most original post punk scene in the country, coloured by liturgical overtones, ethnic rhythms, and sacral imagery. On the other hand, Amila, the sole Bosnian band featured with a song Jutro je već, shows why it was hard to pick bands from this particularly folky republic; the Bosnian slot could have been filled way better with the schizoid guitar noise of SCH, or at least Pauk. Whoever was making the track list was aware of how awkwardly commercial Amila is, and hurried to follow it up immediately with Pečati by Disciplina kičme, Belgrade’s possibly best and beastiest outfit. The ever-inspiring irony about Koja from Disciplina kičme is that, conservative as he is [having spent the new wave era worshipping James Brown, the said Hendrix and lousy 70s yugo rock], and decidedly non-punk, he still made more radical, anarchic and groundbreaking albums than any self-proclaimed punk in Belgrade.

For a Western listener, punk & wave from the ex communist countries have the allure of a forbidden [i.e., censored] fruit. In the case of Yugoslavia, such fascination is, well, for the most part, misinformed. There has been very little, mild censorship, nowhere near as drastic as in Czechoslovakia, for instance; on the other hand, Yugo Punk’s dissenting voices were rarely seriously radical. Just as the anarchic and nihilistic punk in the UK was a natural reaction to that country’s turn towards neoliberalism and privatisation, in the 80s Yugoslavia, as a still functioning socialist welfare state, punk was more about criticizing the system to improve it, not destroy it. Even when it was pissed off [at the grim bureaucracy run by old geezers, sick of status quo and demanding more freedom of expression], the bottom-line message of Yugo punks was usually constructive from the socialist point of view. To advocate anarchy in a functioning socialist state would probably have been just a shallow decadence, and dealt with much more rigorously by the authorities. And although the popularity of punk certainly met some apprehension as a potential threat of the West’s cultural imperialism, it was even hailed by some critics for addressing the local issues from a local perspective, making itself ‘our own’ thing. Thus, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that, back in the day, more than two-thirds of the bands featured on this compilation have found a home for their music, in some capacity, on various state-owned labels.

This openness may seem utopian, but it may also raise suspicion about the bands’ integrity and ambitions towards artistic expression, subversion, and career in general. There are two things to note here: in the 80s Yugoslavia, the DIY ethos and practices hadn’t taken much root yet; such prospects were a blind spot in a culture lacking entrepreneurship. Secondly, instead of drilling their individual paths, bands had a genuine ambition to push the limits of what was culturally acceptable, by boldly taking the public stages. For instance, Pekinška patka, a cult punk band from Novi Sad fronted by a high school teacher turned teenage idol, had a huge success with their debut punk album, but instead of conforming to the safe and sound career as punk’s public darlings, they made their second album an odyssey of depressing post-punk. Alienating the old fans didn’t matter to the band if the new material broke some exciting new ground. The featured song Monotonija is the least difficult one from that particular record.

Besides, let’s not forget what we’re dealing with here – post-punk is often defined by its critique, which is self-critical, less confident and impulsive than punk, rarely direct and aggressive; its protagonists constantly questioning their positions. Instead of a rebellion, these younger brothers of punk painted their bygone reality through self-reflection, indifferent observations, and intricate depictions of their inner and outer world. La strada’s Došla su tako neka vremena excels at that.

Disciplina Kičme [photo by Goranka Matić, by courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade]

There’s a wonderful sense of the moment in those earliest melodies which have, in pioneering stylistic manoeuvres such as ‘Mrak’ by Beograd, reflected the dull monotony of modernist life and revealed the dark underbelly of the conformed society. Speaking of all things dark, mind you, long before ‘goth’ moniker was imported, Yugoslavia had its own equivalent ‘darkeri’ subculture [less peacocky than the scenes in Germany and the UK], imported from Italy through Rijeka, Ljubljana, and Zagreb. Dobri Isak – Ona se igra nožem is a cult classic there.

A word or two more is due about the actual music. Being an admirer of raw, minimal, and abrasive sounds in general, I have always struggled with the sound of most Yugoslav new wave bands. My theory is that the officials in the state-owned labels just wouldn’t let the skeletal esthetics of new wave and synth pop pass, and they tried to make everything ‘more musical’ and ‘lively’ by killing the arrangements with redundant polyphony and unnecessary funky guitars. Praise World Gone Mad Records, they steered clear of such petty musicality on this release, whilst assuring that the selection is still brimming with earworms and melodic hooks. Which was not all too hard, again, given that probably the most influential band for the Yugoslav new wave generation was the ever-so-melodic The Stranglers. From the filthy pub and punk rock, through the stylistic new wave to pop, The Stranglers had it all and were universally revered, ever since their 1978 concert in Zagreb, at their very filthiest momentum. Another UK act, whose concert at its golden peak has sent ripples through the continuum of Yugoslav post punk for a long time, was Gang of Four. Prick your ears and see if you hear it in Trobecove krušne peći – Boje noć u krv.

What a swell album of sonic postcards this is… It’s someone’s noble epitaph to the Yugoslav post-punk and new wave scene. Just as the closing verses of Mrtvi kanal – Slike na mramoru state: i niko ne smije reći da nikad nisam postojao [and no one may say that I have never existed].

Text: Nikola Vitković

Photos header: Paraf rijeka [photo by Goranka Matić, by courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade]

This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.