Tuning into the Earth’s frequencies: Wouter Jaspers on DIY instruments, radio waves and electromagnetic fields

Published July, 2025

by Easterndaze

Wouter Jaspers seamlessly navigates his daily life as a sound artist, instrument designer, researcher and experimenter. He creates tools to explore both the audible and inaudible frequencies of our planet, focusing on the upper atmosphere, electromagnetic fields, the Earth’s natural radio frequencies and even our own body radiation. His curiosity led him to build various DIY antennas to listen to natural phenomena such as lightning, aurora borealis and the everyday electromagnetic smog present in urban environments. This passion for sound led him to found KOMA Elektronik, where he developed the now legendary Field Kit mixer or Sonic Artefacts, whose finely tuned microphones capture the smallest details of the audible spectrum.

Ján Solčáni: How would you describe yourself: as an artist, researcher or instrument designer?

Wouter Jaspers: That’s a very good question to start with! I see myself first and foremost as an artist, and all the other things I do help me with that mission. The making of instruments, the site-specific installations, experiments with radio waves, the exploration of new technologies, and the research are all part of the final process – and that’s to make beautiful things. They can be beautiful in their delicacy as well as in their ugliness, or in the things they can provoke. I believe that I live my life entirely in the service of art.

Let’s go back to the beginning. In your early teens, you hosted a radio show on the local station Centraal FM near your hometown of Bakel. Was that your first experience with the world of radio waves?

My first experience was definitely when I was much younger. I’ve always had a deep fascination with electronics and machines. By the time I was eight, I’d taken apart and put back together every single electronic device we had in the house. Of course, my dad wasn’t always happy because sometimes I’d have ten screws left over.

I used to make my own games, like the wire loop – where you put a little metal eyelet through a wire, and it makes a buzzing sound when it touches. I remember going to flea markets and buying music equipment, radios and cassette players. Afterwards, back in my room, I’d connect this whole collection of machines together. I also made mixtapes and collages for friends at a very young age.

When I was 14, I saw an advert in the local paper – they were looking for someone to help out at the radio station, which was two villages away. So I went there every Sunday. The programme I helped with was about local news and football. People would call in from all the football fields around the neighbourhood with game reports, and I’d sit behind the mixer while the announcer was in the booth. I liked orchestrating and directing the technical side of things.

You were only 14 when you became the station’s technician?

Yeah, 14. They trusted me to do it, which was cool. I was given a lot of freedom. I had to get a key beforehand and open the studio. Everything was very cool and relaxed. After about a year, they gave me my own radio show on Saturday afternoons.

What was your show about, and how long did it stay on air?

It was mostly music with a little chat about what was going on in the town and the region. I was a teenager, so there were some bad jokes and some phone calls. Someone would come in, and I’d just talk to them for half an hour. I once had a motocross rider tell me about life in the international motocross scene. I just interviewed him and asked a lot of weird questions. Classic radio dramaturgy for the mid-90s, but also something you’d call podcasting today. It taught me so much about how to structure a programme. It showed me very early on that everything has a story.

The show ran for about a year and a bit until I was 16. Then it got a bit much because I was playing in bands, and my focus shifted. I got more social, made more friends and had more things to do on the weekends – going to bars, dating and everything that comes with that age. Music took over from radio work.

Still, it was a very formative time. When I think about what I’m doing now, it’s so cool that it all started at such a young age. The same spark of imagination that got me there is still so alive.

At what point did you shift your focus back to the transmission and reception of radio signals and work with electromagnetic fields?

Between 16 and 19, I played in a lot of bands, which was fun, but I always felt that I was more interested in storytelling with music, which was not really possible in the groups I was in. I wanted to have more of an artistic voice besides the music. So I started doing a lot of electroacoustic things. I was 19 and still living in Tilburg, a city with a very nice noise scene at the time.

It was then that I started making DIY instruments, sensors and microphones and using them in live setups. It was a lot about experimenting. That’s also when I started my field recording archive, which means that right now it’s 20 years old.

Do you see this shift towards electroacoustic work and experimenting with radio waves as a natural progression?

I think it was just the next step to bring the stories that I was experiencing into my music and to ground them in place and space. I wanted to create sonic landscapes from outside the room, especially during performances.

In the beginning, it was just three radios plugged into a mixer, all tuned to different types of white noise, and I used the mute buttons to create panned radio landscapes. Later, it evolved into making my own illegal AM/FM mid-band transmissions so I could pick them up and create feedback over the air.

A moment that stood out for me was when my friend Steffan de Turck, who performed under the name Staplerfahrer, used telephone pick-up coils during one of his shows. He combined these coils with an old camera flash. When he pressed the shutter on the camera, you could hear the coil charging, and then when he clicked it again, the flash would go off with a massive burst of light. Seeing that showed me the performative aspect of using pickup coils and electromagnetics.

At that moment, I realised the need to have a performative aspect on stage. I began building more DIY instruments and experimenting with small setups that I could take on tour. Between the ages of 21 and 25, I toured extensively all over the world, primarily performing noise shows. That became my full-time focus during that period.

Tour luggage circa 2009. Photo by Wouter Jaspers

Why was it important to develop your own instruments instead of depending on existing end-user products?

Just the fact that they’re mine. I always like to have a sound or use things that can’t be copied. I view the process of creation as a collection of methods and techniques, and everyone needs to find the approach that suits them best. Personally, I’ve always enjoyed tinkering since I was younger – making DIY instruments, experimenting and pushing the boundaries of sound.

Another thing that really bothered me was that everything was so heavy. Travelling by plane, train and bus with a backpack weighing 15 to 20 kg for three weeks was incredibly difficult. To lighten my load, I stripped the metal components off my machines, leaving just the bare circuit boards. I then put these boards in wooden cases to reduce the overall weight. This way, I still had access to the boards and could easily modify them as needed.

Wouter Jaspers and Steffan de Turck (left) as Preliminary Saturation during a radio performance in 2008

So the wooden enclosures of KOMA Elektronik’s instruments weren’t initially an aesthetic choice but a practical one?

Exactly! Wood is lighter than steel or aluminium, but the choice of a wooden enclosure for the Field Kit also stems from the fact that wood is a great acoustic body. When you place a contact microphone on the lid and run a motor, it produces a warm sound – much warmer than that of metal. I’ve always preferred using wooden enclosures since they allow me to easily drill into them and attach elements like springs, strings and motors. I was doing this long before we established KOMA Elektronik.

So when I designed the Field Kit, it made perfect sense to use wood. This approach has evolved even further with my current outfit, Sonic Artefacts. I strive to use as many recycled or recyclable materials as possible to challenge people’s expectations. After all, why does something need to be made of metal when another material can be just as good, or acoustically even better?

Wouter’s performance setup back in 2020

Let’s focus on the Field Kit for a moment. Back in 2011, Christian Zollner and you founded KOMA Elektronik, and one of the main instruments you developed was the Field Kit. I find this little machine to be one of the most creative and playful electronic music instruments I have ever used. This little box really opens you up to the world. Can you explain why you created an instrument that allows interaction with everyday objects and encourages users to think beyond the instrument itself?

I’ve never thought of it as an instrument. It’s an interface for whatever you’re building. My goal was to create something where the limiting factor isn’t the device itself, but your imagination.

It’s somewhat ironic, considering I previously mentioned making my own instruments to have tricks that nobody else can replicate. But a few years later, I developed an interface that allows people to precisely replicate all my music!

To me, it felt like a good way to get people excited about sound again. At one point, everyone was fascinated by modular synthesisers. While modular synths are fantastic and have their place, I missed the human input in the music at that time. I wanted people of all ages, from children to adults, to experiment with the sounds of the objects around them. Since then, I’ve seen countless people use the Field Kit, and each individual has their own unique approach and ideas about what it should be for them. It feels like a playground.

How important is maintaining curiosity in your work and life?

Creating out of a desire to explore and from curiosity is incredibly powerful. That’s how I got interested in all these things as a kid – just out of curiosity. And it’s the same for me today. I want to keep learning as I create. I constantly challenge myself by experimenting with new materials, new circuits and new sounds.

The most effective approach is to remain curious, ask questions and engage with others. Travelling, observing and listening – whether I’m recording with headphones or not – are essential practices for meaningful work. It’s nice to create from this perspective.

From the installation Ash Transmissions (2025), which focuses on radio and fire

You’ve mentioned listening several times. Why is listening so important to your practice?

It’s like the Dutch saying: “Nee heb je, ja kun je krijgen.” “If you don’t ask, you’ll never get a yes.” If you don’t listen, you’ll never get to the source. You’ll never be able to place a sound in its environment or never catch the essence of the story you want to understand and tell – you’ll just miss it.

If you listen consciously, you can pick up the underlying stories. You can put a sound in its place, in its context. You can take a sound out of its context, which I really like to do.

How does that translate into your compositional process? Are you trying to comment on something when you’re playing around with sound?

It depends. Sometimes there isn’t anything to comment on. I just let the sound be, and it’s wonderful. It can be soothing – it can lull you to sleep. My solo artistic process is a process of collage, especially when I work with radio. I take hundreds of little pieces and try to collage them into a work that evokes something.

These sounds can be anything. I’ve made records with just the sounds from one radio wave, and I’ve made records with hundreds of hours of field recordings from the desert. Sometimes it can be a very small thing that triggers me. I usually start with a motif that I like or a recording that’s about the length that I want my final piece to be. Then I start taking things out, then adding things in, then taking things out again. It’s a constant cut-and-paste situation that I enjoy. It’s probably the only time I’m completely at peace with myself.

Back in 2021, you started a research project called Arctic Survey Music that focused on the ionosphere – the layer of the Earth’s atmosphere that plays a significant role in the propagation of electromagnetic fields and is therefore so important for human communication technologies. What was your approach?

I based my work primarily on the reflections of radio waves from the ionosphere. I experimented with randomly composed music that incorporated rumbles, whistles and very low drone sounds, all of which reflect various natural phenomena like thunderstorms and solar storms. These natural waves can be challenging to capture because human activity has significantly polluted the electromagnetic spectrum. To effectively record these sounds, you need to be away from human settlements, which makes the Arctic the perfect place to do this. I developed equipment to go out there and record these low frequencies on the ULF/VLF bands.

From the results of this research project, I created an installation performance titled Antennenfeld, which I presented in 2022 at the Floating University in Berlin. Basically, it was a symphony created from 32 radio frequencies collected during my research using DIY antennas and radio equipment.

Arctic Survey Music taught me how to filter out specific frequencies and apply logarithmic calculations to transform them into chords and musical motifs that I like. I learned how to perform live with radio waves, ensuring that it felt more like a guided journey through the Earth’s electromagnetic fields rather than just the sound of someone tuning the radio spectrum.

Antennenfeld setup at Floating University in 2022. Photo by Wouter Jaspers

The research was done during the COVID-19 pandemic. Why did you choose to emphasise the ionosphere and sounds inaudible to humans during that specific period?

I felt it was like a blanket over all of us. It’s really interesting to make these sounds audible. It might inspire people to think about the Earth in a different way. We all know that we’re floating around in the universe, spinning on our own axis. Still, the planet is becoming increasingly uncomfortable for humans to live on because of what we’re doing to ourselves. Exposing these sounds and showing the true power of the planet was an interesting angle, especially at that time.

Do the limitations of materiality drive your creative process?

Yes, exactly. It’s beneficial to have external factors guide you in a certain direction. This will always be part of the process of creating, making, developing and researching. To me, it presents a challenge to use specific materials or to find innovative ways to use them.

I have constructed antennas from materials absolutely not made for that purpose. For instance, you can use a tree as an antenna – you just need to tap into its internal waterways, as water conducts electrons. There are ways to use a wooden stick soaked with water as an antenna. What I’m interested in is what waves actually do in combination with landscapes. Last year in Portugal, I worked on a project titled Radio Waves, Mountains and the Deep, which explored how reflections of radio waves operate. I would use various frequencies and highly directional antennas, direct them at a large wall of granite with numerous indentations and observe the signals that bounced back. This involved using natural objects as sounding boards.

You’ll never receive the same signals. Sometimes a jagged piece of granite would deflect and diffuse the waves so much that the return signals became garbled. I’m always curious about what would happen if I sent radio waves in a short direction and then dispersed them. How would it sound when the waves have nowhere to travel? You’re working with both the properties of the waves and the materials you reflect them off. This creates something truly unique – the modulated reflections will sound the way the location designed them.

From the project Radio Waves, Mountains and the Deep (2024). Photo by James Berlin

Has there been a particularly mind-blowing experience for you in your history of experimenting with waves?

Yes, there was one memorable moment when I sent radio waves into a cave and received fractal patterns in return. I got about 15 percent of the sound reflected back, and what I received was incredibly intriguing. When I analysed the spectrogram, I noticed some very unusual harmonics, with a significant gap in the middle of the frequency spectrum. The cave seemed to absorb almost all of the signal, yet it still left enough for me to learn about the phenomenon.

This is interesting because radio signals are related not only to the living, but also the living-dead. Radio waves can outlive their sources, allowing you to tune your ears to past events. How do you approach the concept of time in your work?

The waves travel, right? So whatever you hear has already happened. People often say they want to get their ideas out there, and that’s how I view radio. It feels so immediate, but the moment you broadcast it, it’s over – and once you hear it, it has already happened. You can never go back and capture it again.

In the piece I’m working on for the Floating University in Berlin, people will see movement and hear how their movement changes the sound through radio waves. However, there’s always a delay of a few milliseconds. What you’re hearing has already taken place. Once people recognise their presence in time and can close the feedback loop by moving, they can control time or whatever is positioned on the timeline.

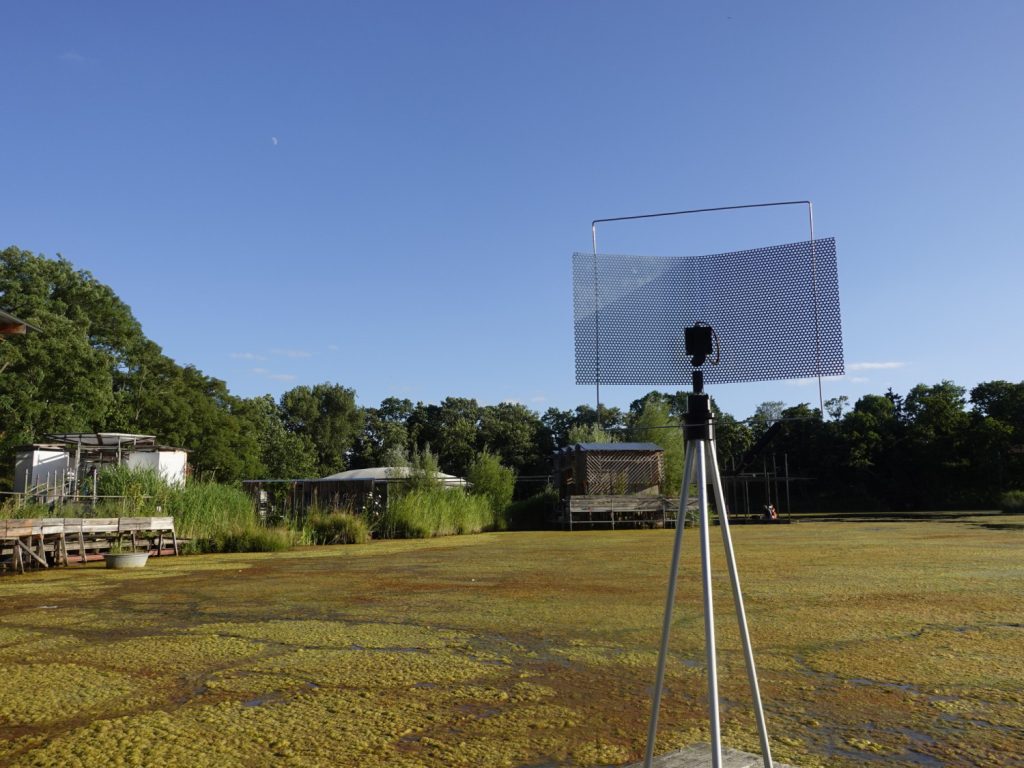

Doppler radar from the upcoming project Urban Interference. Photo by Wouter Jaspers

Can you share more about the upcoming Urban Interference (2025) project at the in)tangible transmissions Festival at Floating University?

Normally, I work with waves that stand on their own, that are very long and, in a sense, very non-human. These waves are created by nature, and while you can influence them to some extent with your own signals, they ultimately represent nature’s radio – the radio our Earth produces. These waves will continue with or without our activity.

But what if I also work with man-made waves? Not music, not speech, but the actual physical appearance of a body. For this installation, I’m using Doppler radars that emit waves which bounce off the human body and return. Instead of having people simply listen to the activity in the radio spectrum, I want them to appear in the radio spectrum.

The location of the Floating University and its walkways allows me to set up the radars where there’s always someone – whether a person, bird or animal – passing by. This enables me to demonstrate the impact of human presence in a man-made natural space within the city, and to showcase what it sounds like. It’s nice for the audience – they’re not just listening to me play with radio waves; they’re actually the source of the waves I’m playing with. The people are the instruments in the end.

Exploring materiality seems crucial to your practice.

Yes, each material produces its own unique sound. Going back to the radio, the choice of materials is crucial. For instance, if you’re creating a Kite Antenna, like I’m building at the moment, it’s best to use copper because specific materials are necessary for constructing an effective antenna.

Currently, I’m experimenting with different materials that are coated with copper. While making a kite that also functions as an antenna isn’t particularly difficult, achieving good sound, obtaining a strong receiving signal and ensuring that it looks appealing are all challenging aspects. There are many physical limitations that I need to navigate.

Sometimes the material itself dictates the sound or the process – in some cases, the material becomes the process. You can’t bypass this – you must work with it. I really like that. We’re provided with various materials on this planet, and we should explore and experiment with how they function.

You mentioned that an important aspect to consider when designing the kite antenna is its visual appearance. This emphasis on aesthetics can also be observed in your other projects, such as Antennefeld and the upcoming installation featuring DIY Doppler radars. It seems that visual presence plays a significant role in your work. Why is that?

I learned early on that it’s very important, especially in electroacoustic music, to make your processes and sources as visible to the audience as possible. When they understand where the sounds come from and can see you creating them in real time, they become much more invested in the work, whether it’s an installation or a performance.

Offering a visual representation of how sound is produced is crucial. It’s even better when they can experience the physical limitations of the medium. For instance, when I’m in performance, amplifying a motor while holding a coil in my hand, I have to hold it in a specific position – if I move my hand too much, the sound goes out of phase. You can do that for a minute, but when you do it for longer, it becomes quite a struggle. That struggle makes it more interesting. It’s nice when people get a little glimpse of the kitchen, and what they see is interesting enough for them to stick around for the main course.

Do you think that listening to the planet has changed the way you understand nature?

In nature, everything moves in waves, and there’s a different kind of rhythm inherent to the natural world. When you listen to natural radio as well as to nature’s sounds, you begin to notice that things operate in cycles. If you record an entire day or night, you’ll hear the birds waking up, then falling silent, followed by the sounds of cars starting up. This intertwining of timing illustrates how nature reclaims space and how humans then re-engage.

I had a particularly striking experience while recording sounds in the forests outside of Berlin a couple of years ago using two microphones and two very low frequency (VLF) band receivers. I was listening to this beautiful forest when, unexpectedly, I heard a massive crash on my VLF bands. A few seconds later, I took off my headphones, looked up and saw a powerful lightning strike. I literally got an advanced warning of the storm over the radio. It was so loud and powerful, yet still felt so fragile.

It’s fascinating how densely packed the electromagnetic spectrum is, especially when using a broadband receiver. At any moment, no matter where you are on this planet, these waves constantly surround you.

Back in my college days, when I worked at a student radio station, I was told that one of the worst things that can happen during a broadcast is dead air – that unintentional period of silence, leading the listener to wonder if the signal has been lost. Is silence relevant in your work?

I believe that, without silence, it’s impossible to create any real impact. There can be no loudness without silence. However, true silence doesn’t really exist, not even on the radio. If you have an RDS tuner in your car and a station goes quiet, data is still being transmitted. If the signal were truly gone, the radio would automatically switch to the next station. You can never find real silence because you’ll always be aware of your own body before experiencing absolute quiet. Even in an anechoic chamber, I found that feeling of complete silence to be somewhat frightening and unsettling. It highlights all the tinnitus I thought I didn’t have. Everything inside becomes amplified.

I try to embrace silence as much as I can. As a field recordist, I always try to find locations with as little distracting noise in the background as possible. Yet there will always be context – the specific location where the recording takes place. That’s what makes it interesting. Even silence on the radio is fascinating – it might make the listener wonder what’s happening. In that way, at least you evoke an emotion.

What are your plans for the future?

In recent years, I have been intensively researching and developing new electromagnetic instruments and microphones for Sonic Artefacts. As a result, I now have a huge collection of recordings and a large collection of tools to play and perform with. Therefore, I’d like to shift my attention more towards creating music and challenge myself to understand all of these newly created instruments not as static objects but as vibrant tools that can capture the world around me in a musical way. For the upcoming year, I plan to stay busy – using my travels and performances to record more, create more, connect with more people, engage in conversations and, most importantly, listen more.

Wouter Jaspers by Wouter Jaspers

Text: Ján Solčáni for 3/4 Magazine.

Originally published by 34.sk. This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthening the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union (EU) or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the EU nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.