Cultivating tenderness through listening with Warm Winters Ltd.

Published March, 2024

by Easterndaze

Bratislava-based label Warm Winters Ltd. strives to weave a tender musical tapestry. Adam Badí Donoval, founder of Warm Winters Ltd., delves into the intricacies of running an independent music label. Reflecting on his journey from DIY beginnings to a more structured approach, Adam shares his commitment to fostering emotional resonance through music. In this conversation, we delve into the label’s philosophy, the importance of tenderness and diversity in music, and the challenges facing independent labels in Eastern Europe.

Ján Solčáni: What is the essence of Warm Winters Ltd.?

Adam Badí Donoval: There is a tenderness to much of the music I release. And perhaps also some strands I follow in terms of the curatorial aspect. I’m trying to build up a roster of artists I work with, over a period of time, some of which have appeared on the label a few times. I find it nice to see their development.

I think the music that I release evokes certain feelings beyond ‟this is cool”. It hopefully cultivates a certain tenderness in the listener.

Warm Winters Ltd. is not your first label experience, how does your current practice differ from your previous projects?

This is the third label I’ve worked on. One was with a friend in London. It was a label that was originally his and later he was happy to involve me in many aspects of the project. It helped me to learn what it means to run an independent label. Later, when I was in London, I started a label that lasted for three or four years. It was very DIY, a lot of the tapes were home-dubbed and without a lot of admin around it. I even printed all the J-cards myself, and those were very limited editions of ambient and drone music. That project came to a natural end.

I still felt this urge to release music and have a platform to curate it, so I started Warm Winters Ltd. There was actually a bit of overlap, I felt that maybe both labels would continue in some way. With Warm Winters Ltd. there is a deeper focus on doing things more properly, leaving the super DIY spirit behind, documenting what’s going on, the finances, working with a distributor, being more diligent about PR and thinking more about scheduling. The idea was to do it in the interest of the artists. To put more care into the work so that hopefully it will generate some income for them as well.

That being said, I work quite short-term in terms of planning. There is always a maximum of three projects in the process of becoming a release at any one time. I’m never sure how things will be received and what kind of return I’ll get. There is generally a lot of precarity among the labels that I know. If the next four or five projects don’t resonate with people, it gets harder and harder to release more work. Especially when it comes to labels that don’t have big catalogues and don’t get a lot of attention on the streaming services. If there isn’t a lot of passive income generation, it becomes difficult to see a long-term future without people’s direct support.

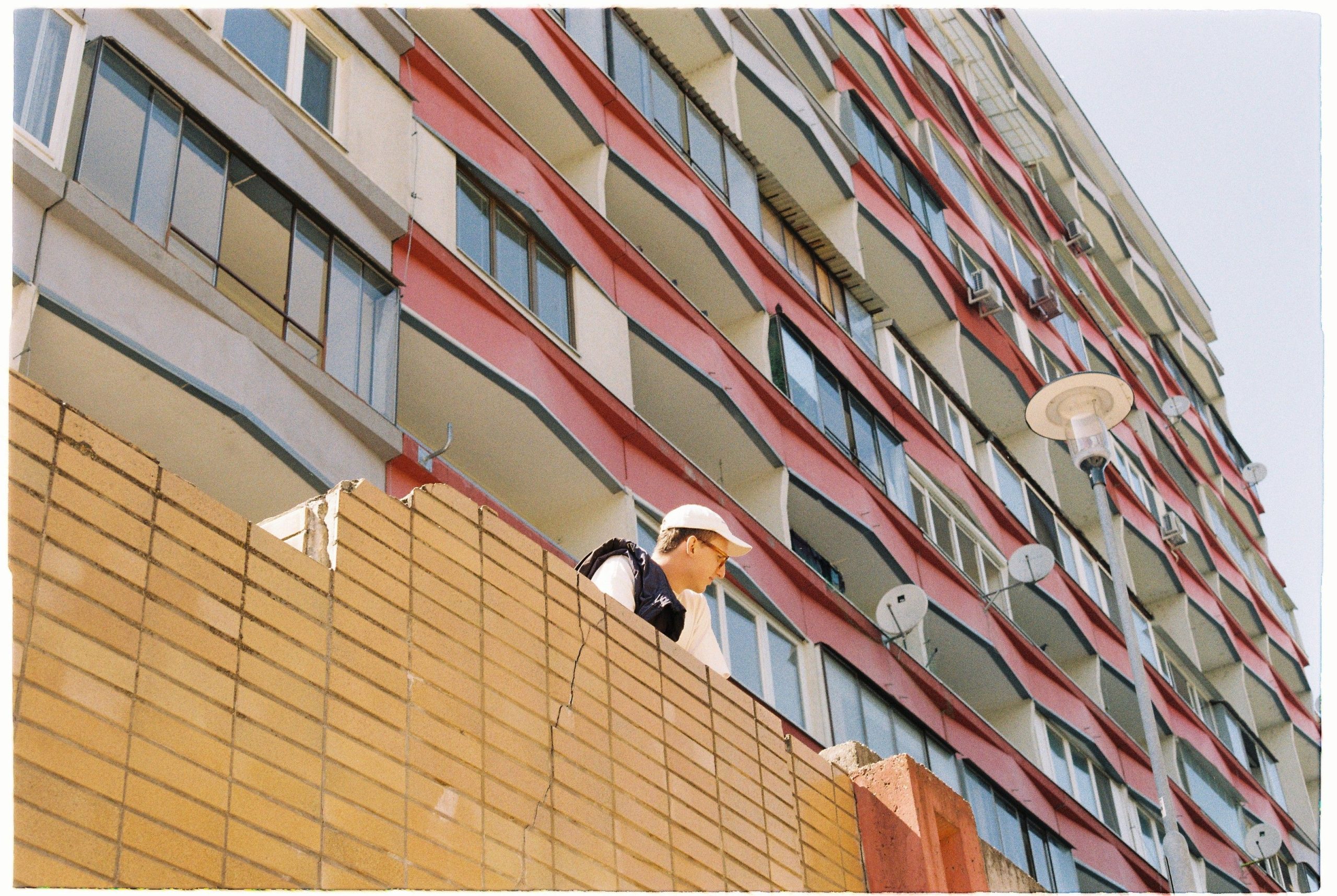

Picture courtesy of Andrea Blahová

I think the unifying element of the Warm Winters Ltd. catalogue is not the genre similarity of the music released, but rather how it affects the listener. What is the concept behind the sound? Can you tell me more about the concept behind this selection?

You’re right, genre-wise it’s quite broad. Some of the music released is very academic, some has a sort of historical narrative and some is super DIY. Lots of debuts too.

What I look for is intentionality and emotional impact. I think the music that I release evokes certain feelings beyond ‟this is cool”. It hopefully cultivates a certain tenderness in the listener. I want it to be something inspiring and also warm and inviting. There is this general sensibility and also the effort to cultivate it in the listener.

Why treat sensitivity as something that should be given more attention?

I’m not sure that was my intention at the beginning. Throughout the curation it became clear that this was part of the framework. I don’t know to what extent that happens. It works for the core of listeners for whom this music resonates and who enjoy this kind of approach. They gathered around those ideas.

What I wanted to focus on is that you approach the label through a number of criteria of what you consider worthy and, conversely, what you don’t. Here I see the element of tenderness as an important aspect of your approach to music.

It’s something that plays an important role. With my practice as a musician, I want my work to point to certain principles of interconnectedness and mutuality. Take it away from an individualistic perspective. Tenderness is an idea that comes through in the way I curate. To be honest, hopefully also in the way I approach communication and collaboration with the artists. I try to work closely with them, to think about their vision. Those things are important to me. Hopefully, that’s how the artists experienced it: as a slightly different experience than just a label that releases records all the time. Sure, I have a pretty strong rhythm, but I don’t feel it’s mechanical, which is nice.

The label is celebrating its 5th anniversary this year. What was the story behind the first album and where do you see the label now?

The first release was a debut EP by a duo from Portugal called Harnes. They both released their solo work (here and here) on my previous label. Someone I work with on a couple of projects. They sent me a new release and that was exactly at the point when I was thinking about starting a new label. I shared the idea with them to release it on a new platform. A fresh start for them and for me. We worked on it with a graphic designer whose designs for tapes and CDs were really nice. From there onwards, it may have seemed like a scattered approach to curation. Now it has become an umbrella and it works! The first release was kind of a pop drone record. I like to explore electro-acoustic, chamber music drone works, process-oriented pieces, and also local scenes within Eastern Europe. Now it’s taking new directions in terms of the albums I have planned for the future. It’s a constantly evolving platform that hopefully still feels coherent.

Do you have any plans to celebrate this anniversary?

We are releasing a compilation of Czech and Slovak artists, so a more localised look at what I like on the local scene. Hopefully, we will have some events in the autumn. There’s a tentative plan to do something in Stockholm and maybe Lisbon and Berlin, but it’s not confirmed yet. We also made some T-shirts and possibly we’ll make some caps or hoodies.

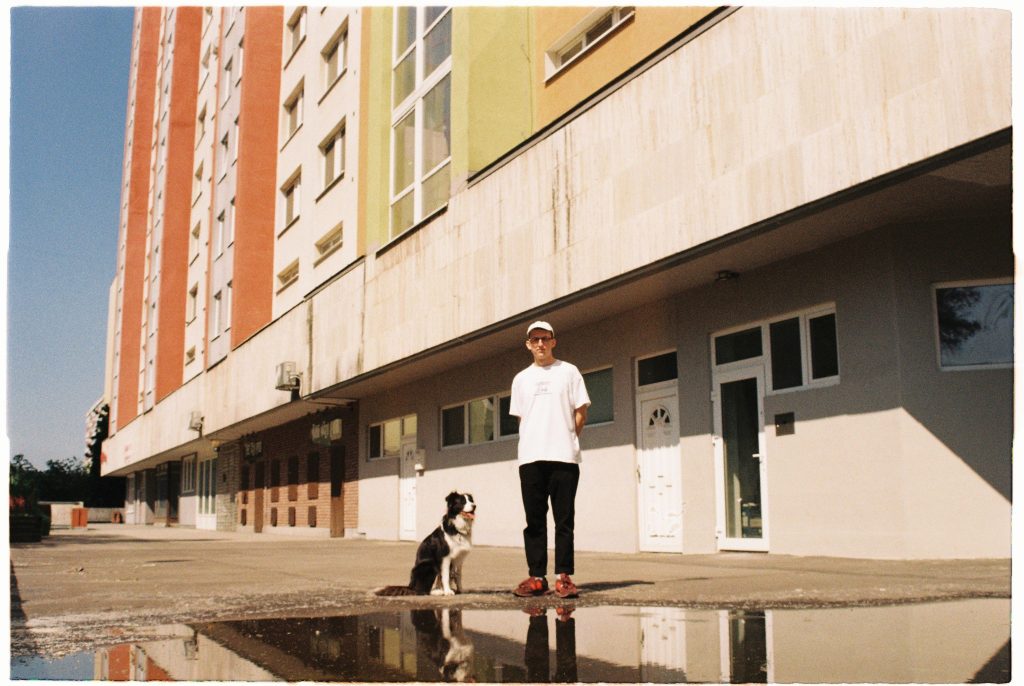

Picture courtesy of Adam Badí Donoval

You run the label from Bratislava, do you see this place as something that in any way influences your approach?

One thing I like about Bratislava is that it’s not in the “centre of the European scene”. I don’t feel a lot of pressure or stress around these releases. It’s something I can do in my own time. While I’ve tried to see the label in the context of a European experimental scene, the fact that I’m here helps me not to feel the pressure or compare myself so much to others. Bratislava doesn’t feel like a very competitive scene. It’s quite internally connected, there’s a lot of mutual support, even in terms of venues, booking and labels. We don’t see each other as competition. We are part of the same ecosystem. I didn’t feel like this in London. Bratislava feels unique in this way. The scene is really welcoming and warm.

What I consider unique is that you have the lived experience of running a label from London and now Bratislava. Are there specific challenges to running an independent label in Eastern Europe compared to other regions?

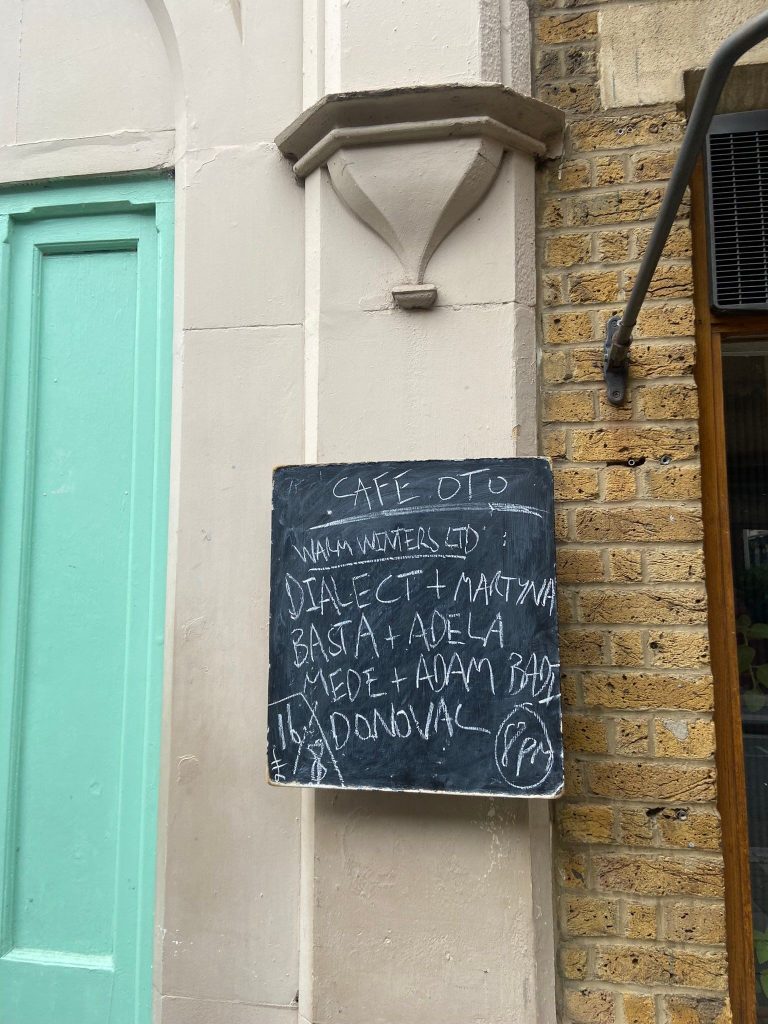

It goes both ways. I think if you frame certain projects as Eastern European or Central European it can be helpful. One of the challenges is that we don’t have as much of a local response to what we’re doing. When Warm Winters Ltd. had a showcase at Café OTO in London last June, it was sold out. Maybe 200 people came. You could physically see the support of a group of people who care about what you’re doing. That doesn’t happen so much in Eastern Europe. There may not be many people who listen to this kind of music that support it very tangibly. Just being in people’s minds is not that easy.

There are times when I think I’m not at the centre of things. That’s something I want to unlearn. If you want to grow and be sustainable, it’s better not to have that attitude of not being at the centre of something.

Picture courtesy of Adam Badí Donoval

Do you think the music and independent label industry and the way it’s approached by the public needs to evolve? Especially in terms of the value placed on music and its cultural and geographical background.

It also relates to the broader conversation around music. It’s often just seen as a very functional area of “entertainment”, but it has the power to shape our culture. To make us think about who we are and who we want to be. That’s a very valuable thing that music can do, and it’s often missing from the discourse around it.

The industry functions on a model that is not sustainable to work within as a musician. As a label, there are ways to operate. You can make it work somehow. Probably not to the level that you pay yourself if you’re on a scale similar to mine. But definitely to a level where the label is self-sustaining enough not to be pumped with a lot of your own money.

For musicians, it is getting harder and harder. The way recorded music is valued is becoming unsustainable. Playing live is harder. Fees are lower and costs higher. Travelling is harder and more demanding. It’s not part of the way people think about music when they go to a concert. They don’t think of it as work that is difficult to sustain. I wonder how that translates into a broader conversation. The input is already coming from a lot of established musicians. They are cancelling tours, it doesn’t make sense financially or health-wise to do it anymore.

Even the way the platform economy is informally referred to is based on the precariousness of being a musician. We label it as the gig economy. There is definitely that connection.

That’s a good point. There’s also often this romantic expectation. You have to suffer to be an artist. That’s not conducive to the best or most meaningful work. In the same way, I don’t think it’s a productive life to live. It’s not dignified.

Looking at the label’s catalogue, I can’t help but notice the diversity of the artists represented. You give a lot of space to non-male musicians who often work outside the global western centres. Why do you think that is important?

It’s partly intentional. I want diversity in the roster, but it is also music that I love. It should be part of the new normal that you release a diversity of artists. In the experimental and especially ambient world, a lot of rosters are very white-male dominated and based in Western “centres of culture”.

It’s important to highlight other voices. That Eastern European focus is true. There is definitely an effort on my part. To seek out people from this region who I think are making music that would fit on the label, to work with them if they want to, and bring their music to a wider audience. I think it’s nice to collaborate with “local” artists.

You mentioned earlier that you like to see an artist develop. Often artists appear more than once in the Warm Winters Ltd. catalogue. The listener has then the chance to discover how their approach has evolved over time. Also, the connection between you and the other person changes. Is that something you’d like to continue?

The collaborations are often so nice that it makes sense to work together again. One such person is Marta Forsberg. She’s a Swedish musician with a Polish background. I think she really enjoys our collaborations. Marta keeps sending me stuff and I keep emailing her about it. It’s also the friendship that develops in these cases that plays a part.

Very few people knew about the work of some of these artists like Tomáš Niesner, Martyna Basta or Ani Zakareishvili before they released on Warm Winters Ltd. It feels like a valuable collaboration, bringing these new voices to the scene. Musically, too, they have a lot to offer in terms of new approaches and points of view. For me, it helps to think of it as a journey that we can continue together.

As we discussed, the world of the music industry is not necessarily welcoming. It comes with a lot of precariousness. Still, there are a lot of young artists waiting for their chance, or maybe they are just too scared to take things off the shelf. Do you have any advice for them?

One thing I have always found valuable is not to think only about your work, but to think about it in a wider context. A lot of my connections have been made that way. What scene am I part of, who are the people whose work I love? Maybe I could reach out to them, sincerely support what they are doing and become friends. That way you start to see connections and places for your work in the music industry. Then, if the time is right, you can release some music with the encouragement of others. It’s not a completely lonely process.

When I think about my first release, live shows and things like that, there was always someone encouraging me. Why don’t you do a release for me? Why don’t you play a show at this event I’m organizing? Those are the moments when you realise that it makes sense. Not to be alone with the music you’re making. That’s a big part of it. What has been the most valuable part of the process of releasing my own music, but also helping others, is giving it context and connecting with others.

Text by Ján Solčáni. Republished from 34.sk

This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.