Dobra Robota: books with a sound of their own

Published July, 2025

by Easterndaze

Gabriela de Mola runs the Argentinian publishing house Dobra Robota, which since 2016 (as she herself defines it) has been publishing non-technical music books in Spanish, using music as a starting point for thinking about people, societies and history itself. It covers a very wide thematic spectrum, ranging from more traditional genres like rock to sonic experimentation, unexpected translations, the recovery of hidden voices from Argentina’s experimental music scene, listening practices, field recording and sound recycling.

I met Gabriela in 2017 when she reached out with the idea of presenting the first-ever Argentinian translation of “The Art of Noises”, the iconic book by futurist Luigi Russolo, at the Centro de Arte Sonoro (CASo). I remember that event as a psychedelic and joyful parenthesis in the midst of a very turbulent time: there were mass layoffs of cultural workers (of which CASo was a part), and the national government was trying to restrict cultural activities with political content, which always pushed us to find preservation tactics to be able to meet and make some noise together.

Since that event, which featured the Italian Luciano Chessa (who wrote the foreword for the aforementioned edition) and South American artists like Leandro Barzabal, Leonello Zambón, Sebastián Rey and Felipe Saez Riquelme, the publishing house has expanded its collection dedicated to music and sound, making it the core of its productions – not only translating, but also producing new content from Argentina. It continued, and I sometimes collaborated, organising workshops, concerts, mediation activities and other public events around its publications. Why have its books resonated so much with the local scene? What communities have gathered around its titles? What is the impact of a publishing house on how a community of makers thinks?

I took this interview as a chance to dig deeper into the publishing house’s editorial work and to expand on the conversations I often have with Gabriela about music, sound art, publishing and communities in our geographies.

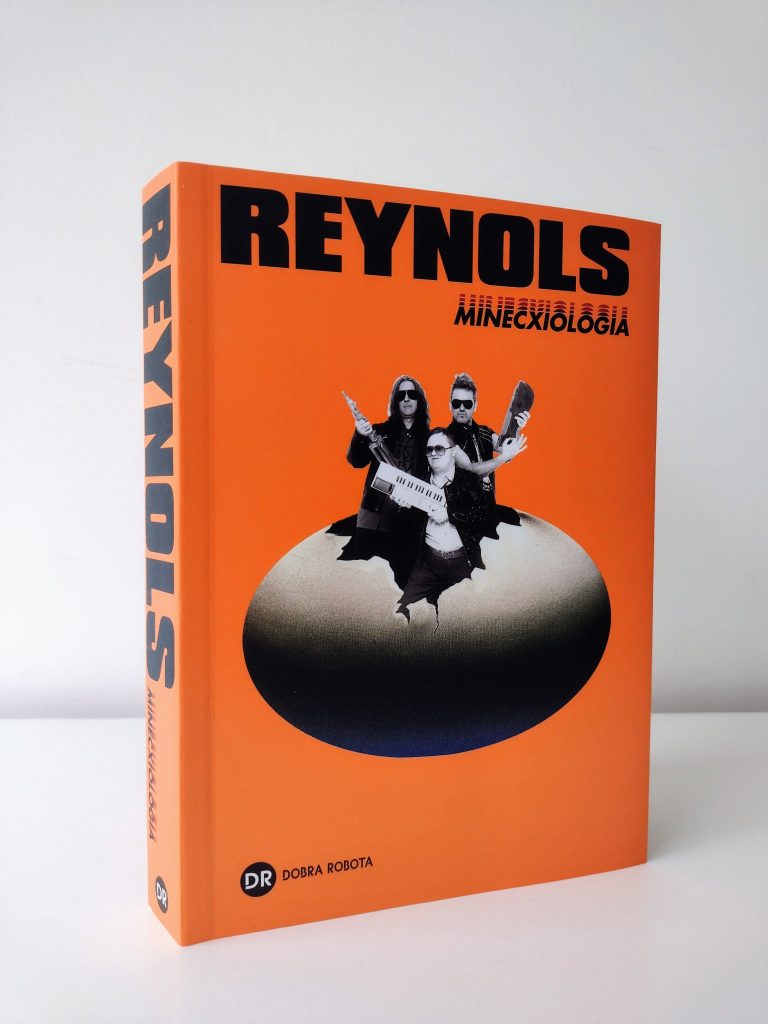

Reynols’ book

Florencia Curci: The first book I’d like to talk about is the one I don’t know yet. You told me that, during 2025, you’ll be releasing a book about women composers in Argentina. What was the research process like? Why do you think it’s important to write about them?

Gabriela de Mola: It was an enormous task. The book is called “Un sonido propio” (A Sound of Their Own). Together with Alma Laprida and Belén Alfaro, we decided to survey the work of several Argentinian women who have worked in electronic and electroacoustic music. We made a selection that’s not exhaustive, but we believe it’s fairly representative. It was almost a detective mission. We wanted to focus on their works, not just the fact that they were women in a male-dominated field. The idea is for these compositions to start circulating in curricula and bibliographies. However, it’s not a technical book: anyone can read it. Something that really struck me during the interviews is that these composers don’t see themselves as pioneers or feminist icons; they simply did what they loved, often without support and while facing obstacles. For me, their sheer persistence is already revolutionary. I remember one interview that deeply moved me, where one of them said: “I never asked myself if it was hard to be a woman doing this; I just did it because I wanted to.” That quiet determination is so inspiring.

Other interesting things emerge, too. When the book is released, it will allow for many readings, because some unsettling facts arise from the texts. For example, the composer Regina Benavente went through a “silent period” of about ten years during which she didn’t compose, and she says it coincided with the time when she was married.

“We started making these books because I felt the need for them to exist, and they didn’t yet.”

FC: Who appears in the book?

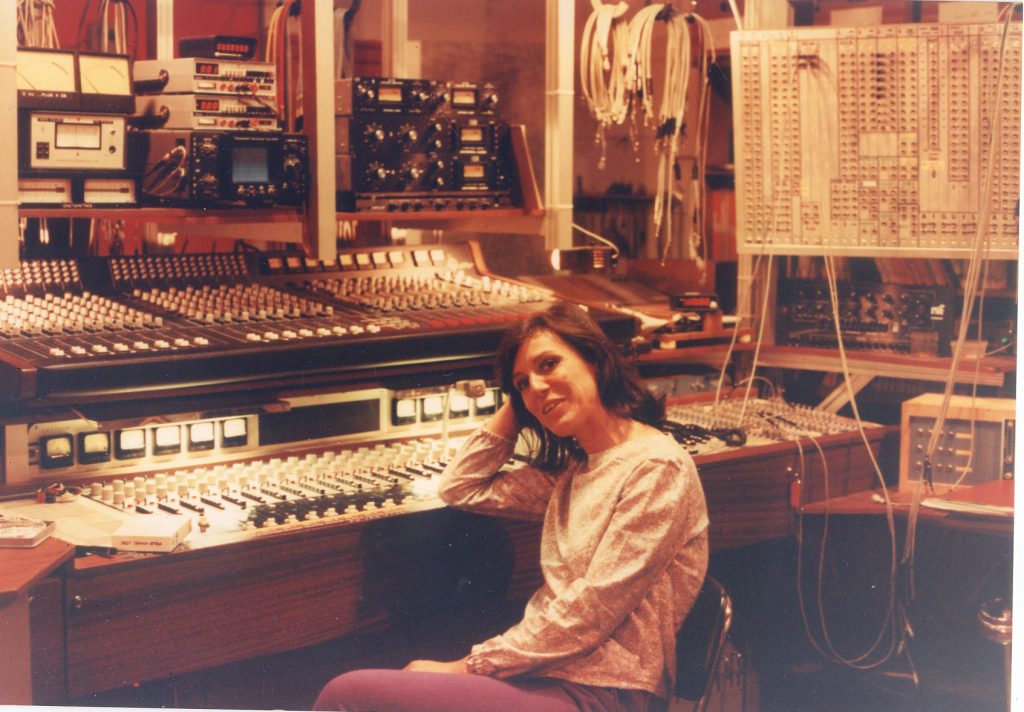

GdM: The composers featured are Hilda Dianda, Nelly Moretto, Leda Valladares, Beatriz Ferreyra, Graciela Castillo, Alicia Terzian, Regina Benavente, Graciela Paraskevaídis, María Teresa Luengo, Elsa Justel, Margarita Paksa, Ana María Gatti and Elena Lucca.

Each research project was carried out by different scholars, artists, musicologists and other specialists, most of whom were already studying these composers.

The book is composed of articles and first-hand interviews with the artists who are still alive. In terms of timeframe, it covers works from the 1950s to some from the 1980s, a period when technological innovations impacted their compositional processes and saw the emergence of very avant-garde, highly experimental aesthetics.

Argentinean composer Elsa Justel in the studio. Courtesy of Dobra Robota

FC: I’m curious about the moment when your publishing house shifted from translating relevant books for Argentinian readers to producing new bibliographic material. What was the motivation behind this shift?

GdM: We started making these books because I felt the need for them to exist, and they didn’t yet. “Un sonido propio” is the third. The first was the book on the Argentinian group Reynols, and the second was “El sonido de las plantas” (The Sound of Plants), a compilation about artists who work with plants and various sound technologies.

Of course, these books take an enormous amount of time and energy to produce, with lots of coordination across different people. The process is very irregular and involves a lot of waiting. But the satisfaction of publishing them is so much greater. Creating a book that didn’t exist before.

With the three books we’ve produced so far, it’s exciting to see how they consolidate the sound work of local artists into print. This will hopefully raise their profile. Creating these books is important because it positions us not merely as a country that passively accepts foreign ideas, but as one that actively engages in cultural and social dialogue.

Gabriela de Mola and Miguel Tomasin (the drummer and the singer of Reynols). Photo by Fran Badano

FC: What difficulties do you encounter?

GdM: It’s obviously very difficult, especially in a country like Argentina, where the economy and politics are so unstable, and you have to constantly adapt. But in the long run, somehow, things get done. You just have to be patient.

FC: So the first “homegrown” book was the one on Reynols? I imagine that process was different from the composers’ book…

GdM: Yes, actually, one book tends to lead me to another. When we translated “Deep Listening”, the foreword was written by Alan Courtis, a member of Reynols. And in conversations with him, the idea for the book came up. This book gave me a huge amount of information. To begin with, it was the first book I made from scratch – it was pure editing work. Roberto (Conlazo) kept recommending other books that helped me think through this project. I even relied on some dreams I had during that period. In fact, I dreamed of the orange colour on the cover.

On the other hand, they have a well-organised personal archive of their flyers, photos, VHS tapes, magazines and all kinds of materials. They sent me 500 photos, already sorted by topic. And they have a lot of unreleased music – that’s where their regular album releases come from, even though they’re not actively playing.

There were many hours of digging through the part of the archive they opened up to me. Looking at photos, listening to records, watching videos and documentaries.

We did two or three hours of video calls per week. Almost everything happened during the pandemic. We would set a topic: today, let’s talk about the US tour, for example. Then, on the weekends, I would transcribe the calls and try to organise the chaos of those conversations – because besides talking about Reynols, we laughed a lot and ended up chatting about all sorts of things.

I organised all the interview material as I transcribed it. I also selected 300 photos from the 500 they had sent me. They were very involved in the editing and proofreading process. In the book, we aimed to highlight their trajectory and emphasise the works that clearly place them within contemporary art.

Reynols’ concert for plants (1995)

GdM: There were many hours of digging through the part of the archive they opened up to me. Looking at photos, listening to records, watching videos and documentaries.

We did two or three hours of video calls per week. Almost everything happened during the pandemic. We would set a topic: today, let’s talk about the US tour, for example. Then, on the weekends, I would transcribe the calls and try to organise the chaos of those conversations – because besides talking about Reynols, we laughed a lot and ended up chatting about all sorts of things.

I organised all the interview material as I transcribed it. I also selected 300 photos from the 500 they had sent me. They were very involved in the editing and proofreading process. In the book, we aimed to highlight their trajectory and emphasise the works that clearly place them within contemporary art.

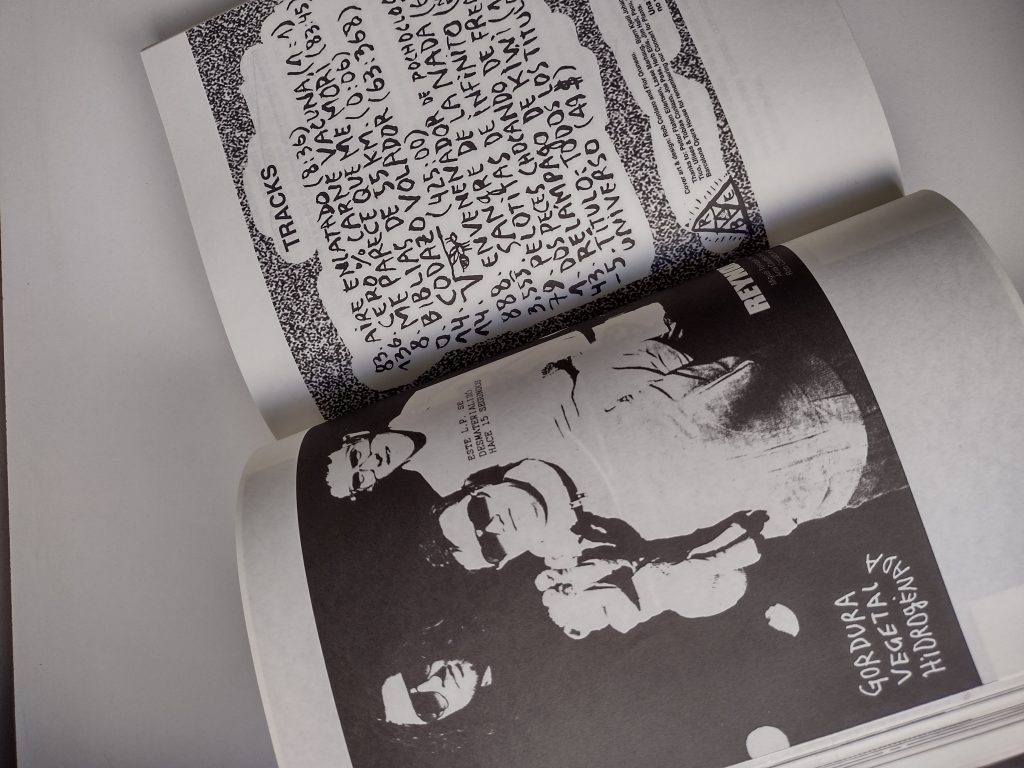

Reynols’ book. “Hydrogenated vegetable fat” album cover and track list

FC: I imagine it was also different from producing “El sonido de las plantas”. How did that come about?

GdM: Once again, one book led me to another. While working with Reynols, they told me that, in the 90s, they had done a concert for plants. It was such a revelation. In 2020, during the pandemic, a Spanish artist did something similar, and there was a small controversy because it seemed like people had forgotten that Reynols had done it decades earlier.

That really sparked my curiosity. I started researching and found that there’s a kind of genre or musical category called “plant music” that dates back to the 70s, with a whole history behind it. Together with Belén Alfaro, we researched the work of local and international artists, conducted many interviews and structured the book around that.

What touched me the most was the tenderness of the intention: that someone would want to place a sensor on a plant to listen to it, even if it doesn’t sound the way we expect, is already such a beautiful gesture. Beyond the sonic outcome, what matters is the search, the connection with another living being.

Miya Masaoka. Courtesy of Dobra Robota

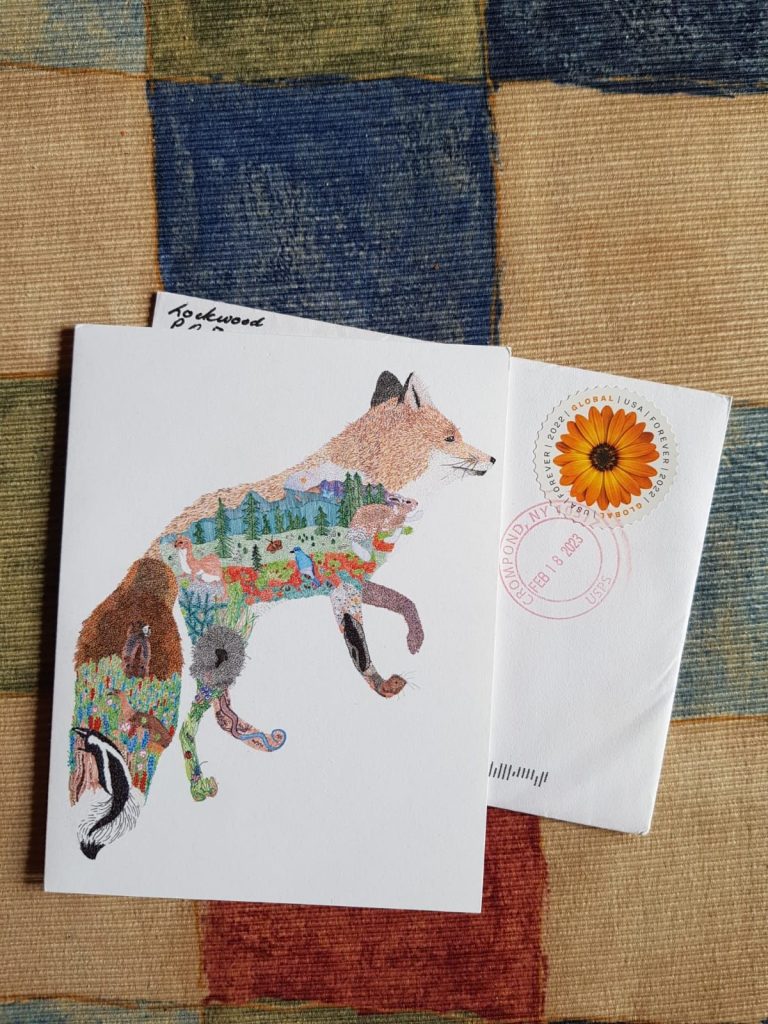

GdM: After the book was published, something really beautiful happened: Annea Lockwood, a truly amazing composer who must be around 85 years old now and has had an impressive career, sent us a postcard saying that she doesn’t understand Spanish but could tell from the photos that the book is fascinating. Imagine that! We keep that postcard like a lucky charm. Annea Lockwood writing to us? We still can’t believe it… We really admire her.

Postcard by Annea Lockwood. Courtesy of Dobra Robota

FC: If one book leads to another, what was the origin? How did Dobra Robota get started?

GdM: I started by publishing Polish literature, because I’m a fan of Gombrowicz. I wanted to publish something of his, but I couldn’t get the rights, so I began with other Polish authors, with the help of the Polish Embassy in Buenos Aires. It was a very formative stage – I had the theory, but was learning on the way how to actually run a publishing house. It was pure desire, almost a personal adventure.

Since I’ve always loved music, I opened a collection dedicated to it. I started with “Touching from a Distance”, the biography of Ian Curtis, which was almost an experiment, and to my surprise, it worked very well. I got hugely excited because I felt like I was truly finding my space. I realised that I infinitely preferred editing essays on music about literature. So I kept going down that path, which almost unfolded on its own, as if the publishing house itself was guiding me.

“I never asked myself if it was hard to be a woman doing this; I just did it because I wanted to.”

FC: What’s your process for choosing what to publish?

GdM: It’s quite intuitive, although I later became very meticulous with each project. I follow what interests me at the moment, but also what I feel might connect with other people. I don’t make five-year plans because I know I’m constantly changing. If I change, the publishing house changes with me. I enjoy letting things unfold organically, following the connections that emerge.

One book always leads to another. That’s what happened with “El sonido de las plantas”(The Sound of Plants), which came from my work with Reynols. That experience opened a door, and from there came the whole exploration of plant music. It feels like a fabric that weaves itself, almost magically.

El sonido de las plantas. Courtesy of Dobra Robota

FC: There’s a very clear focus on accessibility in all your books. Is that intentional?

GdM: Yes, absolutely. I never formally studied music, but I’ve always been very interested in it. When I tried to study, I didn’t have the discipline; I never practised. I remember my classes ended up being almost philosophical because I kept asking my teacher (Seba Pozzi) who had decided which chords should exist. That’s why I edit books that I can understand myself and that anyone can enjoy. I don’t want them to be inaccessible.

I like to think of music and sound as starting points for thinking about other aspects of life. Music is present in everyone’s life, in every context. So I want my books to be read by anyone who feels curious, without needing an academic background. And I also see it as a political act: opening up these topics to more people, breaking down the idea that certain conversations are reserved for specialists.

FC: Why did you choose the name Dobra Robota?

GdM: It means “good work” in Polish. At first, it was because of my connection with Poland and my early publications. But over time, the name took on other meanings. Now I like to think of it as “a good robota”, like a female robot doing good work or something like that. It’s an inside joke that stuck. Plus, I like that, here in Argentina, not everyone knows what it means: it sparks curiosity, it invites questions and investigation, which is very much in the spirit of Dobra Robota.

Originally published by 34.sk. This interview was conducted in Spanish by Florencia Curci. It has been abridged and edited for publishing purposes.

This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.