Terra Ignota: Walking, listening and mapping the unknown in southern Chile

Published July, 2025

by Easterndaze

In the southernmost territories of South America, the nomadic platform Terra Ignota provides a new approach to exploring through radical listening and collective unlearning. For over a decade, Terra Ignota has challenged conventional methodologies, replacing fixed questions with the fluid act of walking, listening and engaging with the landscape. In this space, rocks, wind and found objects become living archives, carrying untold stories and traces of memory.

TEXT Florencia Curci for 3/4 Magazine

PIC Florencia Curci | Nicolás Spencer | Carsten Stabenow

02/07/2025

This interview is part of the southernests series, which explores how certain artistic gestures – through listening, drifting and publishing – activate community or affective bonds across South America (you can find previous articles in this series here). Each piece begins by revisiting personal materials from the interviewee’s archive. These are not private keepsakes, but forms of inscription. Fragments that can blur the line between the intimate and the public, condensing ways of life, embodied knowledge and situated modes of transmission. In this sense, publishing becomes a way of making that blursthe visible and reorganising the common.

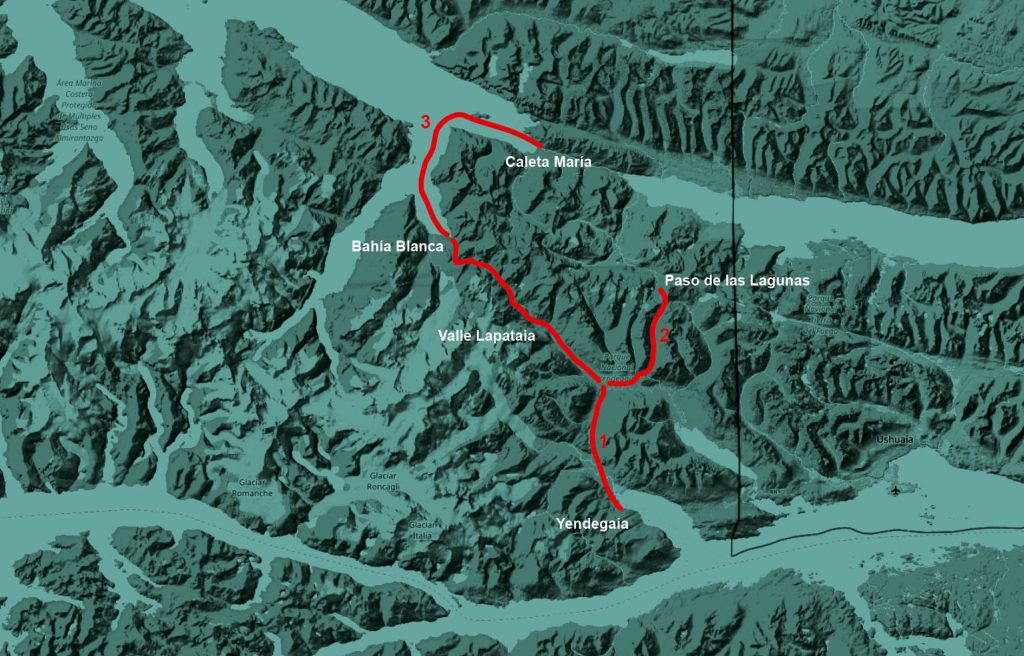

From 3 to 16 March 2023, I was invited to participate in Terra Ignota Forum 2023–24, a cycle of expeditions, exhibitions and collective actions organised by the transdisciplinary research platform Terra Ignota. Since 2015, the platform has developed a recurring nomadic laboratory across the subantarctic territories of Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego and Cape Horn. The 2023 edition was held under the guiding topic of Contact Zones, and the three expedition routes symbolically echoed the possible ancestral paths of the Indigenous peoples of the region: Selk’nam (North), Kawésqar (West) and Yagán (South). I was part of the second interdisciplinary group, which crossed the snow-covered Darwin mountain range on foot, from Caleta María to Bahía Blanca. In my group were archaeologist Robert Carracedo, Fernanda Olivares – who leads the Selk’nam Fundación Hach Saye – and Nicolás Spencer, founder of Terra Ignota.

Location details: 54°49’30.7″S 68°50’53.9″W

The first group walked from Bahía Yendegaia to Bahía Blanca and included philosopher Iván Flores, archaeologist and seasoned guide Alfredo Prieto (who Nicolás refers to in this interview), artist and curator Carsten Stabenow – who, together with Spencer, is the driving force behind this platform – and artists Raviv Ganchrow, Kerstin Ergenzinger and Victor Mazón Gardoqui. The third group, composed of participants for whom the physical demands of the crossing were not feasible, reached Bahía Blanca by boat and established the base camp. That group included architect Cristian Espinoza, Yagán artisan Claudia González, Selk’nam poet Heman’y Molina, geologist Gerd Sielfeld and anthropologist Claudia Augustat.

That experience left a lasting impression on me, not only because of the intensity of the terrain and climate, but because of how it compelled the emergence of a collective body built through interdependence, shared decision-making and deep listening. I understood something there about other ways of researching, other ways of knowing: ways more aligned with movement, activation and intuition.

Although the expedition involved many participants, the full team behind the 2023-24 process extended far beyond those who walked. The walking experience culminated in an on-site forum, where more people joined, and we collectively discussed possible readings and actions rooted in the place. Writers, sound artists, designers, researchers and community leaders (along with lawyers, national park workers and local agents) also shaped the project, forming a wide network of thought and action throughout its multiple phases. This kind of expansive, collaborative work, where knowledge is built relationally across geographies and disciplines, makes Terra Ignota a meaningful case to have in mind, especially in contexts where sound arts and transdisciplinary research gain situated relevance.

In the subantarctic region of Chile and Argentina, various global dynamics (technological, industrial, cultural, financial, energetic, touristic, extractivist) intertwine with local geographies, turning the earth’s deep time into the accelerated time of industry. The tension between ancestral history and an uncertain future runs throughout the landscape. Cultural traces and ancestral markings coexist with new extractive operations and emerging data infrastructures alongside canoe landings, ancient fishing systems, improvised sculptures, recent fishing industries and speculative eco-tech ventures. Notably, green hydrogen has emerged as a regional focus: Punta Arenas hosts Enel’s Haru Oni pilot plant, producing synthetic e-fuels via wind-powered electrolysis. At the same time, the H2V Magallanes initiative brings together major energy firms to develop large‑scale green hydrogen and ammonia installations. These projects coexist in the same territory once navigated by Indigenous communities and subsistence fisheries, overlapping without necessarily integrating, revealing complex, material frictions. Terra Ignota’s work dwells in those frictions, listening to what resists categorisation or legibility.

In this interview, I speak with Nicolás Spencer, who has led Terra Ignota for over a decade. Through a series of drifts and displacements, we explore the complexities of the southernmost region of the world by revisiting some of the project’s sound installations and listening-based practices.

Florencia Curci: I asked you to bring a few objects from your personal archive that might help us get closer to what we do in Terra Ignota. What did you bring?

Nicolás Spence: I brought three tools. They represent ways of thinking. Each of them accompanies me differently when we enter the landscape, and each of them comes back changed when we leave. Let’s start with this field knife. It was a gift from Jorge Quinteros, who, for me, is a kind of teacher without a school. A man who walked across Chile before satellite maps even existed. Jorge was among the first to cross the Southern Patagonian Ice Fields. He gave it to me during a difficult moment, when I was trying to understand what exactly we were searching for on these expeditions. Many years ago, he told me that getting somewhere wasn’t the point. That we had to learn to stay still. He was like that: he could be a hundred metres from the summit and stop. “You can see everything from here,” he’d say – not because he wanted to see more, but because that was enough. That stayed with me. That the summit isn’t the goal. The path is what shapes you. In Terra Ignota, we take that seriously. We don’t explore to conquer. We explore to listen. Another thing I find interesting about this knife is that you were the one who mentioned it as a possible object to bring to this interview. So, in a way, it wasn’t really my idea – it was yours, or ours. It speaks to one of the core ideas in Terra Ignota: that thought is something we build together.

FC: Is this the same knife that got lost?

NS: Yes. After a rather traumatic expedition in Punta Arenas, I lost this knife in Bahía Mejillones (Navarino Island, Cape Horn region). We had a collaboration with the University of Magallanes that fell apart in the middle of the process. It was rough. There was tension, misunderstandings. The group fractured. And after that chaos, the knife disappeared. A year later, we returned to the subantarctic region. With a different rhythm, different people, a different way of being. More silence. More care. And in the middle of a hike, in the mud, the knife reappeared. Right there, at my feet, one year later. I picked it up and felt as if the land had answered. As if it was saying “it’s okay. You can continue, but with more care”.

FC: And what happened to the sheath?

NS: The original had rotted. It had been exposed for months to the weather, to saltwater. I went to a cobbler to ask for a new one. He listened in silence to my story and then told me his wife had dreamed of a similar knife. That he couldn’t give it to me without telling me that. I never fully understood what that meant, but it felt right. The object wasn’t just mine. It carried other stories. It had passed through other hands. For me, that’s what a real tool is: something that not only cuts, but also traces relationships. Like the knife, Terra Ignota passes from hand to hand, from story to story.

FC: What’s the other item from your personal archive that you brought for this interview?

NS: My skin. Though I didn’t bring it, I live in it. It’s the border that both separates and connects me. On long expeditions, when you spend days walking without signal, without paths, often without words, your skin begins to function differently. It becomes porous. There are moments when you stop feeling like a separate unit. You become part of the system: you, the river, the wind, the tracks, the insects. Everything vibrates together. In those moments, skin becomes a zone. A crossing point. A site of extended perception. It’s a tool we didn’t invent, but one we can refine.

FC: Did you bring anything else?

NS: Yes, a jacket, my rain jacket. It’s the opposite of skin, but necessary. It’s a barrier. An exoskeleton. It protects me from the weather, the mosquitoes and the brutal cold. But at the same time, it isolates me. It separates me from the world I want to feel. It’s a contradiction – like all technologies. We use recorders, GPS devices, inflatable boats and camp stoves. All of that is necessary, but also problematic. The more gear you have, the less permeable you become. In Terra Ignota, we try to inhabit that contradiction without resolving it. The jacket, like the knife, is also an archive. If you look closely, it holds traces: dried mud, salt, rust stains, loose threads. It’s portable memory. A way of carrying the landscape with you.

FC: A similar idea orbits around your work with rocks, right? The idea of understanding certain objects as witnesses or containers of stories. Objects that carry information. How did that work begin?

NS: It was gradual. At first, we went south (to Fuegian Patagonia, which includes Tierra del Fuego, the Patagonian Channels and Cape Horn) without a hypothesis. We wanted to understand by walking. There was something in that territory that returned questions to us. On one of those walks, an archaeologist picked up a small stone. It was a flint shard. He said, “Something happened here.” He began to recount the landscape through that stone—what had happened, or what might have happened. He linked it to Indigenous people, to Julius Popper, to gold prospectors… there was a lot archived in that one fragment. That stayed with me. I understood that the landscape was full of invisible signs. The territory was an archive, but one that needed present bodies to be read.

FC: How did the stone collection work?

NS: We travelled over a thousand kilometres on foot and by boat, moving from the mountains to the sea. The journey stretched from Seno Iceberg Fjord (around 52.8°S, 71.3°W) in the northern part of the Magallanes region, all the way down to Cape Horn (55.0°S, 67.3°W) at the southern tip of South America. We also crossed from the mountain range at Sierra Baguales (51.5°S, 70.8°W) to Madre de Dios Island (55.1°S, 67.7°W) or the coast of Tierra del Fuego near Puerto Yartou (54.9°S, 68.1°W). It was a long, physical route, sometimes very silent. We moved in small groups, paying close attention to what the territory was telling us, seemingly empty places where we found stories stored in witness rocks, like hard drives archiving events. We took these rocks, positioned well to record those moments in their core, along with us on a temporary basis to offer this narrative through a sound sculpture.

FC: How did the rocks collected during the expedition become part of Rocas, the sound installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Santiago, where they were suspended from piano strings in a large-scale resonant structure?

NS: We gathered a varied collection of rocks, but we weren’t selecting them for how striking or unusual they appeared – we were looking for relationships. Each rock activated a possible story. They weren’t mute objects; they were supports. As if they could hold time. Real hard drives. We brought them to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Santiago and built an installation. Transporting them was complex – they travelled in custom-made wooden boxes, some weighing over 90 kilos. The installation was called Rocas. Each rock was suspended from a 14-metre-high resonant metal structure using long piano strings.

We worked with restorers, luthiers and assemblers. It was a highly technical, yet deeply emotional setup. Each rock made the strings vibrate with its own resonance. The tension of the piano wires responded to the rock’s weight and balance; the rocks were asymmetrical, shifting subtly with air currents or the movement of people nearby. These micro-movements generated vibrations that travelled along the metal strings and into the resonant structure. Since we didn’t use any amplification, the sound emerged directly from the material interactions: gravity, friction and the acoustic properties of the space itself. What you heard wasn’t the rock itself, but the length and tension that held it, the air, the echo, the people around it.

FC: How were those rocks narrated?

NS: Each rock was related to two postcards, one describing the “objective information” like size, geological origin, the place where it was collected, etc., and the second postcard with a story. These stories were a poem, a tale, a scientific speculation, a vocative expression and a reflection made by the sea. It didn’t matter whether the stories were real or not. What mattered was that they opened up a possibility of reading. It was a vibrant, emergent archive.

FC: Who participated in the project?

NS: More than a hundred people. Poets, scientists, carpenters, sound recordists, translators, editors, restorers, installation technicians, transporters, photographers. The list is long. And still incomplete. Because there were also those who told us things along the way. Or those who appeared later, listening to the rocks. Authorship didn’t make sense. I asked myself not to sign it. It was a collective work, in the most radical sense. A work that cannot be closed or claimed.

FC: What happens to a rock when you take it from its place?

NS: It changes. It becomes something else. It loses something and gains something else. Like when the knife sank into the mud. Like when it came back with a new story. Rocks are like that, too: objects that transform through contact. We don’t treat them as “nature,” but as companions. As bodies that carry memory. Some we returned. Others are still travelling. In exhibitions, in boxes, in conversations. And each time someone touches or listens to them, something changes.

FC: And how does that connect to Terra Ignota?

NS: Completely. The way we think of Terra Ignota lately is like a non-hierarchical archive. There’s no centre. No index. No final version. It’s a lab for collective interpretation. The rocks are part of that. Like the knife. Like the wind. Like errors. They’re transmission supports. We’re not trying to fix meaning. We’re trying to activate listening. The rocks don’t explain. But they do make sound. And that, for me, is enough.

FC: In a conversation we had while caught in the wind of Patagonia, you mentioned the idea of wind as an object. This also comes up in your piece Osciladores, where you explore wind as a sonic and spatial force. What does it mean to you to think of wind that way?

NS: It started when we were working with communities in southern Chile. It has to do with the lack of understanding. At first, I went to that territory thinking the cultures that had inhabited it were gone. But they weren’t. Some cultures are said to have left no objects, or left so few that it’s hard to identify them. In the Yaghan culture, for example, when someone died, the community would burn their belongings. They even erased the person’s name from their vocabulary. If someone were called John River, you could no longer say that word, “river” again; it was erased. So you had to say, for example, “the water that runs.” So all concepts were mutating all the time. Memory didn’t depend on accumulation but on transformation. I was really struck by that. It challenged my understanding of archives, one that doesn’t preserve or fix. And I started wondering: what remains? Often, it was the wind. The same wind that hit the elders hits me. That wind travels. That wind continues. So I asked myself: could wind be an archive? And I began to understand it as a cultural object, a hyperobject1.

It is also, in a way, a way of construction or perception of space. The idea of wind as a home, as a nomadic territory, also challenges what we mean by “nomadic” in the first place. Maybe nomadic is also the way you move from the kitchen to the bathroom. Maybe they were nomadic, too, but within a larger house. A repeated set of movements that creates a place without fixing it in objects. It has no walls, but it structures space.

FC: How do you work with a conception like that?

NS: The first thing was accepting that it couldn’t be controlled. You can’t store wind. You can’t master it. But you can tune into it. So, together with the metal sculptor Diego Cortés, the luthier Tomás Elgueta, the architect Osvaldo Sotomayor, the restorer Diego Ahumada and a group of engineers (I’m an engineer, too), I designed a structure that would resonate with the wind. That would activate itself, without electricity, without performers, without text. Something that only worked if the wind blew. We built sculptures made of strings tuned to the pressure of the wind. And just like any other structure that vibrates, they fall apart as well. Technically, it was unfeasible. Everything should have collapsed. But we persevered. That persistence helped us understand that wind is tied to the Earth. The structures were anchored with a system inspired by a corkscrew, not something you drive into the ground, but something that embraces it. Like the fruiting body of a mushroom, what you see is just part of a larger underground network of mycelia. This body of work became known as Oscillators – a series of wind-activated sound sculptures. Each piece is named by its exact geographic coordinates and the length range of its strings. For example: Oscillator 54°55’51.2”S 67°39’17.6”W / 953–1176 cm.

FC: Where were these Oscilators installed?

NS: In several places, all quite remote. No signal, no marked paths. We didn’t want the work to circulate on social media. We wanted it to exist only in the moment someone heard it. The string system changed with the weather, with humidity. Some days, it didn’t make a sound. On other days, it could be heard hundreds of metres away. We never knew what would happen. And we liked that. It was a tuning instrument. If something happened, fine. If not, also fine. That was part of the learning.

FC: And who was the sculpture addressed to?

NS: At that time, I was thinking about genocides. On a personal level, the one my grandmother lived through during Pinochet’s dictatorship. And one on a collective level, the genocide of the Selk’nam, Kawésqar and Yaghan people. When harm is far away, by language or geography, it doesn’t hurt the same. There’s a distance that makes it feel unreal. That’s why sound matters to me. Because it forces imagination. The sculpture could be heard for kilometres, but since it was isolated, it was as if it didn’t sound at all. Some sounds aren’t heard with the ears. But they’re there.

FC: Here again, the wind is an archive.

NS: Yes. But not a traditional one. No shelves. Not something that’s stored. Not something you consult. An archive that moves through you. Like a language that disappears if you stop speaking it. Like a story that vanishes if no one listens. The wind is a carrier of something that resists being fixed. In Terra Ignota, we work with that. With memories that can’t be preserved, but that persist. It comes back like a gust. We put our bodies there to tune into it, even if just for a moment. Even if nothing remains afterwards.

FC: What materials do you work with at Terra Ignota?

NS: With words, bodies and technologies. We record a lot, we talk a lot and we walk. Conversations while cooking, wandering or debating what to do next. Discussions about logistics, rhythm and whether to camp or not. We even record things we never listen back to, or revisit years later. It’s a way of working with what gets lost, with what appears only afterwards.

FC: What do you do with those recordings?

NS: We transcribe them in a very open way. That’s where our idea of making “cartographies” comes from, like this map. But they’re not maps for orientation, they’re maps for dismantling. We don’t aim to represent the territory as something stable. We try to show how it moves, how it vibrates. Sometimes the points on these maps aren’t physical places, but moments, gestures, decisions, questions, problems. A crossing, a word, a silence – some things can be more significant than a location. Another nice example is the video “A journey in the great archipelago”, which we made in 2023, addressing the early humanity movement towards Antarctica.

FC: What’s the method underlying these works?

NS: Turning the map around. Taking it as a tool for getting lost, not for arriving. Dismantling linearity. Listening to crossings. Letting the materials say what they need to say. We don’t explain. We don’t complete. We want to activate unexpected connections. The archive isn’t for preservation, it’s about making contact with what’s still in motion.

FC: Do you share the results of your work in publications?

NS: We don’t think of it as traditional publishing. It’s an archive that keeps breathing. That can change every time someone opens it. We don’t want to determine the way to read it. We want to host a listening. So that whoever enters it hears a vibration and says “there’s something here for me”. Each expedition, each mediation, each exhibition can be considered part of that archive.

FC: What’s next for Terra Ignota?

NS: We’ll keep moving. The shape is uncertain, and that’s part of the method. What remains is the commitment to walking, recording and being affected. We’ll follow new questions and tensions that don’t seek answers. It’s often uncomfortable, always contradictory. But it invites us in. It insists. Like the wind, like the archive: it stays open, alive, unfinished.

This interview was conducted in Spanish by Florencia Curci. It has been abridged and edited for publishing purposes. Originally published by 34.sk

This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthening the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union (EU) or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the EU nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.

Footnotes

1. Philosopher Timothy Morton introduced the concept of “hyperobjects” to refer to things that are so massively distributed in time and space that they transcend our usual modes of perception. Examples include global warming, nuclear radiation and even the biosphere. Hyperobjects do not reside in one place, but “stick” to us and shape our reality in ways that are difficult to grasp.