“Love cannot tolerate laziness” – Interview with Sándor Vály

Published July, 2025

by Easterndaze

Sándor Vály moved to Finland in 1990 and has gradually turned to audiovisual art over the last three decades. We talked about his beginnings, his musical development, personal and collective art.

Luspy: When did you begin working with music, and how did it start?

Sándor Vály: Let’s skip the background, because it would be a too long introduction, as I would have to talk about a process that would be the story of the identity of a young man, aged 14-15, or rather the story of his birth. It has been a very long and sensitive process, born out of the musical, artistic and literary experiences that have defined my existence and my place in the world, as I have lived it every day since. Music was part of this process, first passively and then actively. This activity gave birth to a language that was akin to the underground of the time, and so the recognition of this tribal language dissolved my loneliness. My early musical experiments were made under the drawn of this language. Acoustic and electronic experiments, sometimes alone, sometimes with short-lived bands.

Perhaps the first band that you have any musical trace of was Niskende Tewtär in the late 80s.

Niskende was founded around 1987-88 with Attila Kalóczkai and Vali Fekete. Attila had just come over from the disintegrating Zajártalom and had ideas that were perfectly in line with mine. By this time we were really bored with punk. We wanted to do something different. We were interested in a concept that combined sensitivity with wildness, poetry with ecstasy, music with visual arts, creation with chaos. Of course, the technical possibilities available to us in the 80s did not allow us to fully develop it, but I think that everyone suffered for it at the time. Military conscription thinned the band, and by 1990 we broke up without any real documentation. Apart from a few poor quality C-tapes and photographs, nothing was left behind. We bled out slowly.

What was the Hungarian underground music scene like back then?

The underground music scene of the 80s has been described by many people. Many of us lived it in many different ways. I only knew one segment of the underground, although there were of course overlaps. By segment, I mean that I obviously had an overall picture and experience of the underground, but often these layers went side by side. I’ll give you an example: if Zsolt Machát hadn’t shown me Tormentor, I probably would have passed it by. Tormentor was quite an extreme layer of the underground that was out of my horizon. For that I am very grateful to him.

These layers were also present within Niskende. Attila Kalóczkai and Imre Apró came from Zajártalom, Viktor Csányi went from Cséb 80 through Trottel to Lenin Boulevard, until he finally reached Korai Öröm. Attila Zsámán came from Pszichó. Zoltán Márkus from some punk-ska band. Károly Ludvigh represented the world of improvisational jazz and folklore. I was there at the first rehearsals of the ancestral ‘Fegyelem’ in Benczúr Street and the first concert in the school, then I dropped out. In other words, everything from punk to industrial music and hardcore was present in the band, while I was neither at Psycho nor at Cséb-80. I knew they existed, but I was still moving in a different circles.

The scene was lively, vibrant, never boring—always something happening. There was something in the air that was very inspiring for me and obviously for others who were not only consumers but also creators of that time.

Yet, in 1990 you left Hungary and moved to Finland. Why did you leave and why Finland?

In 1989, I met my Finnish wife in ‘Tilos az A’. What my wife was doing in Budapest is a very complicated story, which has its roots in the Romanian revolution and the death of Ceaușescu. My wife’s ex-husband was a political correspondent and was in Romania on assignment for the Finnish radio.

We fell in love the moment we met (34 years ago). There were two options. Either we would stay in Hungary or we’d go to Finland. I already had one foot out of the country, so there was no question that the second option would work. I made the right choice. I learned what democracy is, what acceptance is, what equality is, what freedom is, what it is to be left alone. I also learnt what it means to live in darkness for months and what insomnia means… So yes, I left for love.

You also continued to make music in Finland, the first tangible release of which – correct me if I’m wrong – was Non Ultra Descriptus. You had already produced this together with your wife, the artist Nea Lindgren, and it departed from the world of Niskende both in its instrumentation and its atmosphere. What were your inspirations and how did N.U.D come about?

I was working two fronts. First I tried to revive Niskende with Finns. I was working with very professional musicians, but I had constant problems with the drummers. I was used to Viktor Csányi, who could play the drums like a beast. It was unacceptable for me to do worse than the original sound and vitality. After a year I gave up that attempt.

At the same time, I bought my first 8-track C-cassette mixer, which I then started working on with my wife, the painter Nea Lindgren. It was Non Ultra Descriptus which was experimental industrial, noise music.

Those were very strange times. The children came one after the other. Meanwhile I was learning the language and trying to integrate into social and cultural life, as I was working in audiovisual art. The cassette Early Works 1988-92, released in 2023 on the Finnish label New Polar Sound, is an honest record of those years.

Nea Lindgren & Vály Sándor – Non Ultra Descriptus

The move away from the world of Niskende was influenced by many things. Niskende was about freedom, its immense desire and madness, to which Attila Zsámán’s incredibly powerful and beautiful poetry gave a bursting form. Zsámán was an ecstasy for me. This form was transformed when I moved to Finland. The world around me changed, the language changed, the culture changed, and through that, a lot of things changed in me. Finland has made me an adult, a free man with responsibility. It was then that I realized that I had previously lived in a society whose citizens were not allowed to grow up. I was living in an infantile society whose basic attitude is similar to that of a tyrannical father and son, in which the child learns professionally to be afraid, to lie, to bargain, to conform or to escape. It is a situation that is terribly distorting for society and the citizens who build it. Progress stops at one level and starts to work as a loop for decades, or even for centuries.

I suddenly found myself in a world where these “norms” were not present. I felt free and I had to do something with that freedom. Non Ultra Descriptus is a medical terminology, roughly meaning “more or less undefined”. That’s how I felt at the time. Something was happening inside me that I couldn’t define at the time, but it started a process where redefining myself showed me a person who sees himself and the world as an adult. I experienced moments of self-identity. I no longer had to deal with things that I no longer considered part of me.

These were internal transformations that were not always moments without drama for my spiritual and intellectual development. I had to absorb and process these information and confrontations. The imprint of this inner spiritual process is Non Ultra Descriptus. A time of change. And this change squeaked, whistled, crackled, and then suddenly turned into a soft piano chord whose notes were still being scraped with sandpaper.

This internal change has been accompanied by external changes. On the one hand, the acoustic change, which is closely linked to Finnish nature, and on the other hand, technology. For the first time I had access to electronic instruments, samplers, looper, computers which gave me a great opportunity and joy. I started to experiment without limitations.

One material after another was born: I released them in limited, numbered copies on cassettes. This required a label, which was never registered. It was the abbreviation for N.U.D., Non Ultra Descriptus, which in turn also referred to nudity. And at that moment I was totally naked.

What was the music scene like in Finland back then?

In the 90’s I was not really in the picture, but I had the opportunity to work with people in the experimental music studios of, for example, Finnish radio, who were quite well connected and slowly introduced me to this world. But because I was absolutely going on my own way, I didn’t really follow what was happening. Sometimes I’d pick my head up when I heard something new, but it didn’t have much of an impact on me. Of course, I happened to be at the first Apocaliptica, Radiopuhelimet, Cleaning Women, etc. gigs. Jussi Lehtisalo, the frontman of Circle, was our record producer. At house parties, I had discussions with Pan Sonic, Jimmi Tenor, hardcore figures from Northern Finland. These were important encounters, but they weren’t inspiring for me, apart from the fact that I knew that these figures were building and building the Finnish underground. I wanted to pursue my own way.

As a record label you mention Jussi (Ektro Records), but before that you released a couple of albums with J.K. Ihalainen on N.U.D. and Hypnopoliittinen Instituutti. I suppose I’m not missing the point by saying that these labels were made by you and were “author releases” rather than publications? How difficult or important was it to get your material physically published at the time? Did you try to find a publisher or did you print the CDs yourself straight away?

In answer to your question, I had to look into my past. I have 29 CDs and 12 C-cassettes running under N.U.D. records. The Hypnopolitical Institute was a side project of the Finnish poet J. K. Ihalainen’s publishing house. There we released 9 CDs together. Both were, and still are, fictitious labels. If I can’t officially release material, or I’m having a too prolific period and don’t want to burden the labels, I release under N.U.D. The downside of this is that it gets a lot less attention, as I don’t do any marketing, I don’t have any connections with music forums. In other words: I’m insanely lazy. And I have no sense to promote and sell myself.

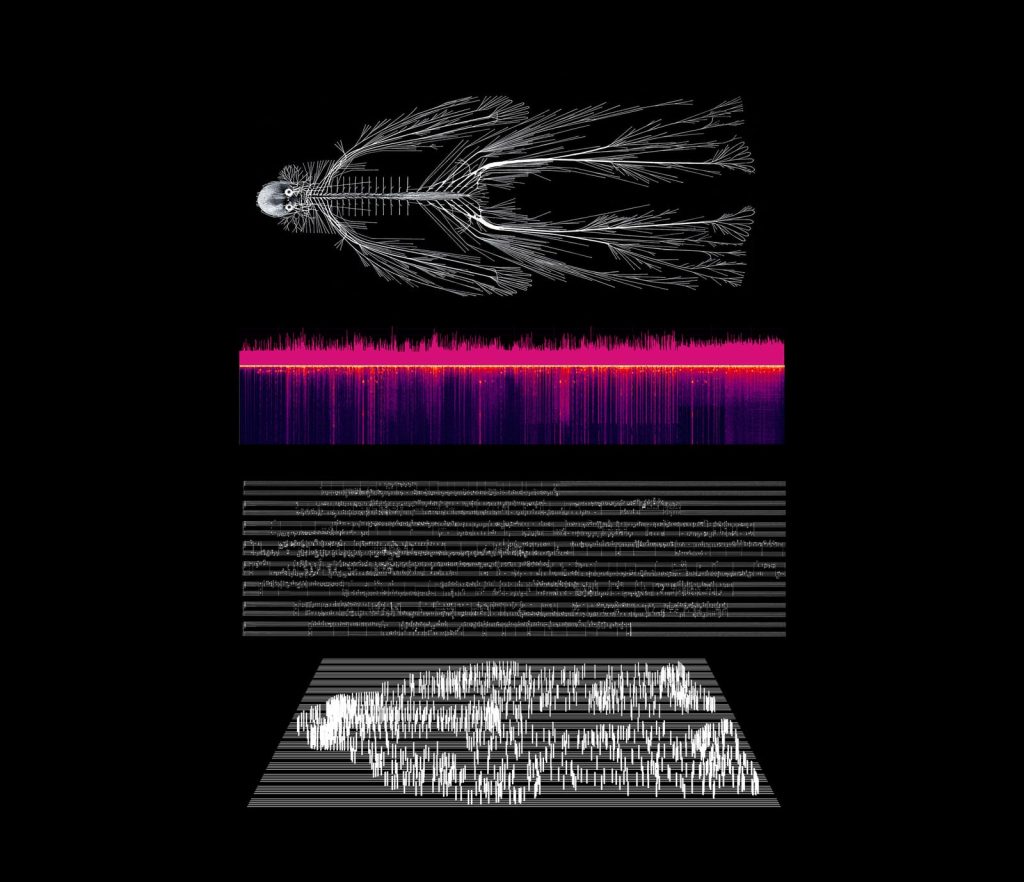

That said, it is of course important that what I do reaches the listener, in a physical format – not to mention that for me the physical presentation, the visuals, are as important a part of the release as the music itself; in many cases they add extra information to the understanding. An example of this is Milky Way and Nervous System (Ektro 2021) – a project with Eva Polgár – for which the visuals (booklet graphics) were essential to understand what the hell we had been doing for eight years. It is not easy material.

Polgár Éva & Vály Sándor – Milky Way and Nervous System

Coming back to your question, the publications of N.U.D. and Hypnopoliittinen Instituutti were author’s editions, without any serious background. I was fine with that, it never occurred to me to look for a label. I didn’t think anyone would be interested in what I was doing.

But then Ektro records came along.

Ektro Records is a success story. In 2011 I had a concert at the Pori Art Museum at the Finnish Night of Arts. I was sitting in the backstage when a large, kind bear settled down next to me. It was Jussi. We introduced ourselves. When he heard my name he exclaimed “I’ve been following you for a long time, but I didn’t really know who you were, what you looked like, where you lived”, etc. That night we agreed on the release of the Mondrian Variations. After the release he told me: “after this record, whatever you do, I’ll release it”. That’s how we released seven albums on Ektro.

After Jussi threw in the towel as label, I was in trouble. I didn’t think I’d ever be so lucky again, that someone like me would ever get a label again. I was wrong. Around Andrey Tischenko’s art gallery in Helsinki, there was quite a massive underground community, one of whose ‘lodges’ was made up of musicians – as Andrey also organised concerts in his gallery. It was here that I met Manuele Frau, the head of the newly formed New Polar Sound label, who produced as their second and third releases the Early Works 1988-92 and our collaboration with Attila Kalóczkai, “The agitated calm of insubstantial space”. And the icing on the cake is blindblindblind, who released on vinyl the Prayer album. These are very nice things.

I can’t help noticing that your musical works are mainly with collaborators (Ihalainen, Éva Polgár, Júlia Heéger, Attila Kalóczkai) and they are also notated in this way, preserving the two composers. What does this duality mean to you, what does it express in the creative process?

I would proceed in order. Ihalainen is a very strong Finnish poet. He is a provocateur, very sensitive to social and political issues, whose sense of justice, language, humour and strange Dadaist associations always raise the reader’s eyebrows. We met at an exhibition opening in Lapland in the early nineties, where I immediately sensed that his poetry was not born in rooms. Ihalainen was poetry with his life. Somehow my recordings got to him and he asked me if I wanted to work with him. Over the next 26 years we did many projects, performances and concerts together. Without any pretension, I can say that in Finland we created a form of stage poetry that was connected with music, performance and often shocking background films, which in this way – poetry, performance, music, background film – was a real shock for many people. We had a lot of scandals. I enjoyed absolute freedom in this collaboration, but at the same time it was important for me to represent his poetry audiovisually. In other words, I was bringing ideas to the music and film that I would not have done on my own as a project – but at the same time it was a great testing ground for my later works.

That said, I like and can work with women much better. I need the kind of communication that is created between the two sexes in the course of a creation. These are secrets that are sometimes revealed in the creative process, through the music, and reveal something of the mystery that is an essential part of my life. Perhaps it is my fascination with the feminine part of Adam Kadmon, who is divided in two. The desire for unity in creation.

Eva Polgár and I have always created in a complementary way, which means that we have taken into account both feminine and masculine principles when developing musical themes and concepts and divided them between us. The most beautiful example of this is the ‘Mondrian Variations’ and our subsequent album ‘Gilgamesh’, where it was very important to bring feminine perspectives into a masculine world. Gilgamesh is very balanced musically, precisely because of the intellectual and emotional perspectives and divisions. The method was a continuous communication. We were left with volumes and volumes of correspondence after each record.

With Julia Heéger the concept is different. Methods evolved along the way, and they are still changing today. Our works run on two tracks. One is the sound and audiovisual installations that we present during exhibitions, and the other is the music and audiovisual works that are specifically designed for concerts and presentations. Of course, sometimes there are overlaps, where a piece becomes a sound installation, or vice versa.

Julia is a pleasure to work with because she can surprise you so much. Let me give you an example that illustrates this very nicely. I mostly bring the themes. Something is born in me – an idea, an experience – that stays with me for years. I go around the idea a thousand times until I am convinced that what I feel is important about the subject is beyond me. So it is not a question of my embarrassing desire to communicate, wallowing in the trap of self-mythology, but of something that goes beyond myself and affects man himself, humanity. When this feeling is born, I start to work.

Our last album, which we finished last autumn – The End of the Tragedy – was originally intended to be quite dark in tone. Deep bass organs, industrial noises, disharmonies, etc. So I had a massive concept. However, I don’t like to give instructions. I never told either Eva or Julia what I thought or imagined for a theme. Of course, if I was asked, I answered. (It should be noted that Eva lives in the United States and Julia in Finland. I am in Italy at the moment. So it’s not so easy to collaborate physically.) So we arranged the trip, Julia arrived at the studio and I showed her the subject. Of course I had an idea of how the piece should sound, but I didn’t put it on Julia’s head. I wanted to see how she would feel and react to the music. I started the recording, which was rolling without light, in a dark tone, and Julia began to slowly unfold a baroque theme on it. I thought I was going to fall over. Into this darkness Juli brought light. It was like a feather falling from the wing of Lucifer, who has fallen into the abyss, which suddenly begins to shine and gives birth to a beautiful fairy called Freedom. Julia’s reaction to the piece was amazing. At that moment I knew why I loved working with her. Because she is not there to please—she is there to serve, she creates. There is a huge difference between the two. So in short, the joy of knowing the other gender is what I enjoy in music.

Vály Sándor & Kalóczkai Attila – Sardinia 2023. – Photo Nea Lindgren

And finally Attila. This was a special challenge, which I described in the CD booklet. The fact that we hadn’t actually met for 30 years. When I moved to Italy, on my 50th birthday, I met him again and Vali Fekete gave me the idea to do something again. We both shied away from doing something retro or comeback. We soon found a point that was a challenge for us. Two like-minded people, who have lived the last thirty years in two different spaces, cultures, social and political environments. Their youth, their manhood. We started to work with these experiences of life and destiny. A discourse emerged, in which I brought the music and he brought his experience of life in Central and Eastern Europe. They were very hard texts, which he was able to turn into poetry with his own sensitivity. It was a serious challenge to work on these texts because, although I am a master of crises, suffering is not my basic experience.

So, dualism is most fulfilled in my collaborations with women, because it is truly a holistic relationship and process that always holds surprises and joys.

On the other hand, you also have solo works, of which I would perhaps highlight Young Dionysos, where you specifically take a piano to pieces. What does that symbolise?

Young Dionysos is a personal story, very positive but without being dramatic, about the ancient experience of collectivity and community that I had when I was 15 years old in Greece at a Dionysus festival. That night I went through everything that would be enough for a lifetime. It was an experience I have been processing for more than thirty years. It took me that long to formulate for myself what happened on that night, which introduced me to the world of eroticism, horror, beauty, drama, ecstasy, madness and, last but not least, music and art. I have captured the birth of a young man’s identity, the experience of this dramatically lucid moment. This experience of feelings that cannot be linguistically classified or identified led me to a catharsis that totally changed the way I saw the world and to the articulation of which I began to engage more seriously with art.

Since you intended a more in-depth interview, let’s not be short on words, especially about Young Dionysus, if you really want to understand the motives behind the destruction of the piano.

That night, the vortex of Dionysian collective visions and images sucked me in, where the human was present as an image of the not-yet-created, manifesting itself as a work of art. The still intoxicated, untouched image of man, dissolved as a part of the ancestor-one, raging without consciousness of his individuality. It would have been impossible for me to reflect on this at the age of 15, because I would have needed the other half, Apollo, who was able to change from the created into the creator. I did not know this then. Later, it was precisely the reflection on the Apollonian side that dragged me into the crisis of my own separate existence, which I experienced as a fall, because although I recognized the Apollonian, despite all the joy it gave me, it also meant separation. It was a feeling of being alone, and not least of being divided.

I later discovered the roots of this division in Christianity, which attempted to weave a dream of man that was unable to live up to, because man was a stronger reality than the dream of him. He wanted to see himself as something other than what he was. He repressed his sexuality, which became a neurotic perversion, imbued with a deep fear of death, and finally imbued with a deep fear of life.

Sexuality and death. Two great scandals, two great elemental themes. Both of them struck back like neuroses. The body as a scandal; degraded, repressed, forbidden energies and became self-destructive parts of humanity. Fear of death, frustration, aggression… Everywhere we find the unmanageable, hell-bound part of us screaming for a way to break free. This was the moment when Young Dionysus came together. I began to see these unmanageable and unbalanced forces as a field of energy that I wanted to work with.

I started thinking about how to harness and integrate these energies. How can these two energies work together and how can they be expressed in the language of art. And so the work was born, which has grown over the years into a complex Gesamtkunstwerk. Film, dance, text, music, performance, installations, exhibitions. One version of this was a series of concerts performed over three consecutive evenings – this is the documentation of the album material – aimed at arousing the layers below and above linguistic rationality. To evoke the energies of the creative and destructive forces acting on us and the world, which I wanted to integrate in the performance.

When thinking about the concert, I needed a strong, awe-inspiring, massive, spiritual and not least a percussive instrument with which to articulate such a work. That is why I chose the piano. The technique with which an instrument is played should not be a limitation for me. I have never followed any rules in either visual art or music. If it’s a percussion instrument, then obviously my technique is an alternative way of playing it. An instrument without a human being is a dead object, only man can endow it with transcendence through himself, only through him can it gain meaning. Destruction is only an illusion. The destruction of an instrument, but not the death of its idea.

This was helped by my friend Sunny Seppä, who recorded, sampled and looped the sound stages of the piano’s destruction in real time at the concert, which he then played back to the speakers, and to which I reacted. This cycle resulted in continuous growth, organic creation. At the end of the concert, a symphony was born from the sounds of the shattered piano in front of the audience.

Sándor Vály – Young Dionysos

Dionysus and Apollo were together. The created and the creator, who cannot exist without each other if we are to live and to live a healthy life. We need the knowledge that let us know and understand the secrets of integrating energies. As I see the world today, I increasingly feel that we live in a destructive chaos of energies.

By the way, the album contains not only the concert recordings, but also a vocal theme sung by my son. He was about my age on that Dionysian night.

I think it is important to note that there is a long tradition of smashing up the piano. I did not invent it. The Fluxus movements were already seriously engaged in it. But the aim of my work was not to shock, but to choose an instrument that best suited my aim as stated above.

I am not familiar with your work as a painter, but for some reason you expressed this experience in music. Why? Why have you moved away from painting towards music over the years?

Young Dionysus went beyond the limits of what could possibly be condensed into a painting, a two-dimensional, radically limited and exhausted form. Painting is always a condensation, while film, music, performative arts are the unfolding of a story through time in space. These different emphases can be compatible with each other if they are conceived in the spirit of the “Gesamtkunstwerk”. Otherwise it would be impossible. Thus, my move away from painting is very much linked to Young Dionysus and the process of confronting the dilemmas that preoccupied me at the time. For me, painting could no longer satisfy the expectations in which I could have expressed and articulated the human being.

But music, film and performances all pointed me in the direction of what I saw as a viable path to a solution. Sound installations and music were an excellent way for me to unfold stories in space and time.

Considering that you are active in both visual arts and music, the question arises: why can’t music have a larger audience in contemporary and modern, not to say experimental, arts, as opposed to visual arts? While the work of Rothko or Tapies is widely accepted, Stockhausen (not to mention others) is almost exclusively met with a reluctance.

You have asked a very difficult question that is almost impossible for me to answer. I have my feelings, but I am not at all sure that I see the problem correctly.

I don’t think the experience of art can be learned or taught. You either bring some sensitivity with your birth or you don’t. If you have this sensitivity, whatever happens in life, sooner or later this language will open up and through it you will be able to better understand the part of the world that remains forever hidden to others. When this world is opened up, it is of course important to continue to investigate things. One explores, reads, watches films, goes to concerts and exhibitions, where one sometimes has strange, surprising, funny, shocking, disturbing, meditative or activating experiences that either support or challenge one’s values, identity and relationship to the world, in other words, one is constantly intellectually and emotionally engaged in an intense life. This intensity continually inspires one to follow these happening, because these happenings are about the contemporary man, they are an image of him.

Art is exciting because it can tell you an incredible amount of information about people. If you look at Pieter Bruegel’s paintings, you’ll know exactly what and how the children of the Dutch region played with in the 1500s, or what emotions his English contemporary William Byrd put into his music. For me, Rhotko’s paintings or Stockhausen’s music are no different from Bruegel’s or Byrd’s, as they all documented their time, the eternal contemporary man. So they are authentic. Once you understand that, Stockhausen is not so alien to you.

We could also talk about the conformist and opportunistic intellectual laziness of our time, caused by the bleeding and collapsing class of the bourgeoisie born in the Renaissance, and its disappearance in culture by the 20th century, or about the impact of the individualism of the 19th century on artists, who were given both the sense of freedom and the sense of abandonment, and to do something with them. The centuries-old ties that had bound the artist to the ‘client’, that had kept him in symbiosis, were broken. This moment opened the way for the first time in the history of man and art to focus their work not on the external world, but on the exploration and revelation of man’s inner world. The individualist artist emerged, who began to delve into the depths of himself, bringing to light his personal visions of the world and of himself, in the hope that his private visions would meet the experience of the recipient and potentially form a new community, whose relationship with culture would no longer be about the glorification and service of power, but about the freedom of the individual, the expression of his emotions and thoughts. Subcultures, trends, styles and ‘isms were born, which demanded intellectual vigilance from the individual. This was a process in which many people bled to death because they were lazy to follow the changes, even though contemporary art is about contemporary man and his situation.

There’s a filter, a barrier in us that makes us constantly delayed in reacting to ourself – you don’t always understand the age you live in. Art, even philosophy, can help, but you cannot approach it with intellectual numbness.

For me, music is much more intimate than visual art. Obviously because we have to open ourselves more deeply to music. I have often been moved in front of pictures, but only music has been able to bring tears to my eyes. Music touches the mystery of our human existence to a depth that can reach down to the atomic level. Music is a magical language for a simultaneously intimate and collective immersion into the deepest layers of human existence. The “image” is an adventure and reflection in the outer layers of the world, while music is a journey into the depths of the human being. Perhaps that is why music is more difficult to receive, because we have to open ourselves to it in the same way that we do in love. And love cannot tolerate laziness.

Text and English translation by Tamás Luspay

Lead photo Niskende Tewtär

Originally published on the MMN Mag

This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.