To understand and unmake this world, we need to become it first

Published July, 2025

by Gyula Muskovics

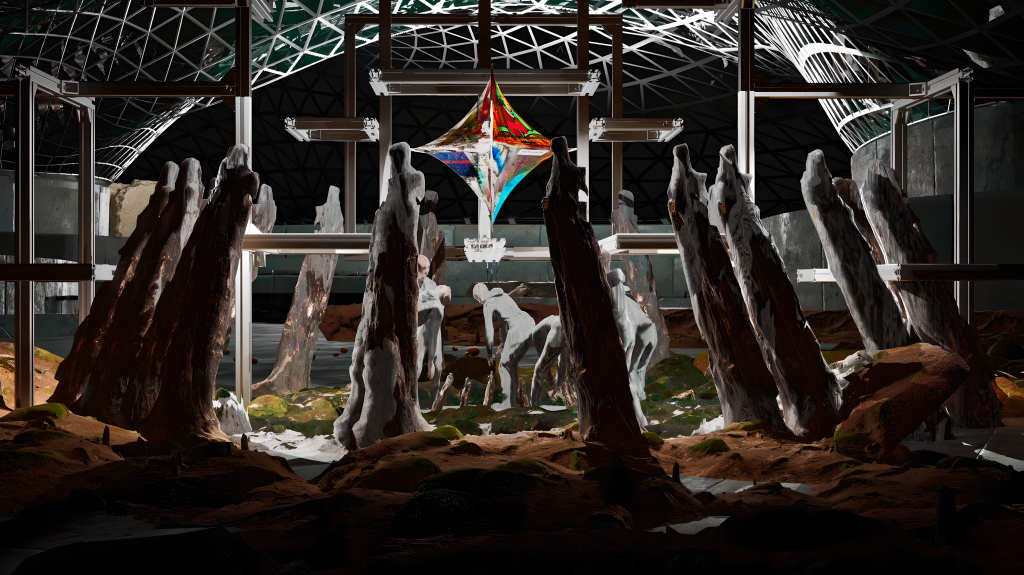

I have been friends and collaborators with Tamás Páll for many years, but his latest video work, Rumble, was even a trip for me—in a good way. The 20-minute-long story begins to unfold in a hangar filled with Cybertrucks and pallet structures. On top of one of these structures, we see a window, anxiously opening and closing, that turns out to be the main character of the piece. Window—which I really like as a name—greets the audience (i.e., the viewers of the installation at the gallery), introduces itself, and tells that it used to be a future-making surveillance machine. When the intro ends, it rises into the sky, flies away somewhere in a lithium mine, and shares a vision with us. The story is about a group of extremophiles that are capable of existing beyond representation and rationality. They put a spell on Window, and that is how we slowly arrive at the rumble—a sound that is different from anything it has ever experienced; something that you become in the moment of revelation, which is, in Window’s case, the moment of transformation.

This conversation took place on the occasion of the exhibition Emergency Frequencies, where Rumble premiered. The show—featuring artists like Nikita Kadan, Tuan Andrew Nguyen, or Lawrence Abu Hamdan—was part of the 5th OFF-Biennale Budapest (May 8-June 15, 2025), Hungary’s largest contemporary art event. OFF came to life 10 years ago as an independent “garage biennale” with no state support in response to the government takeover of Budapest’s major art institutions in the first few years of Viktor Orbán’s regime. The main topic this year was “security”—an ambiguous concept often invoked and distorted in public discourse nowadays. The exhibition that Rumble was a part of showcased video works and installations that represent, manipulate, play with, transcribe, deconstruct, recompose, or overwrite the sounds of war and conflict.

The inescapable materiality of sound in Rumble appears more as a liberating force and less as something that has to do with war and weapons. Since I found this new piece by Tamás pretty enigmatic, with unintelligible mantras and secrets that can never be unlocked, I was mainly interested in the lore behind the work. In a way, this interview serves as a collection of side notes to the video that help make sense of the ungraspable, which is the essence of Tamás’s world-building process in general. Rumble, on the verge of realism and fantasy, shows us how absurd it is what we call reality, and at the same time, suggests that undoing could be a form of resistance against hegemonic regimes.

Before getting into more detail, can you tell me: Why a window?

The character called Window condenses and recombines multiple references to symbols and technological phenomena that surfaced reality in recent years, like the Tesla Cybertruck or machines used in industrial prototyping. In the world of Rumble, Window is a body without organs (or rather, its organs are aluminum rods, language, and virtual environments), a hollow entity that tells a story of its own transformation—a transformation that is fueled by self-destruction, surveillance, and a self-inflicted trans-species erotic love affair.

Rumble 2025 – Tamás Páll – film still

So, Window is an absurd take on the Cybertruck?

Yes, partially, among other things, it tries to evoke the geometry and feel of that truck —maybe it fails in that attempt, though. I wanted to push the material and aesthetic qualities of the Cybertruck towards a more absurd edge, where the masculine and meme mining qualities of a hyper edgy contemporary car and tech design dissolve into the mundane, and the marvel of engineering becomes an ancient piece of technology, i.e., a window. This transformation is not complete, though; it is in process, prone to fail as it enters another fantasy, the world of the film.

Window appears in the installation, too, as the frame of the screen displaying Rumble.

The laser-etched frame that encapsulates the 10-year-old TV screen goes beyond the Cybertruck reference—it is a metallic carrier of a mantra that is almost impossible to read. It is a mythical poem in the story as the origin of transformation, yet the viewers can never hear or read it. The combination of the mundane with fantasy and magic results in this weird artifact that produces both the physical body of Window (the installation) and a gateway to a secret that can never be unlocked.

A mythical poem that can never be read and a secret that can never be unlocked. Got it. But where is Window flying?

As the story starts, Window flies over a vast grid of Cybertrucks set in a hangar near a mining pit. This opening scene sets the context for Window’s transformation; it seems to be a flashback from its past, where it was part of a surveillance system, guarding the trucks and the mine. It is kind of like a bad joke that a sophisticated automated surveillance system is represented as an object that is ridiculously simple. Then Window’s path leads from the truck hangar to a commune that is riding, licking, caressing, and essentially hacking a similar truck. And here we enter the dream sequence of transformation.

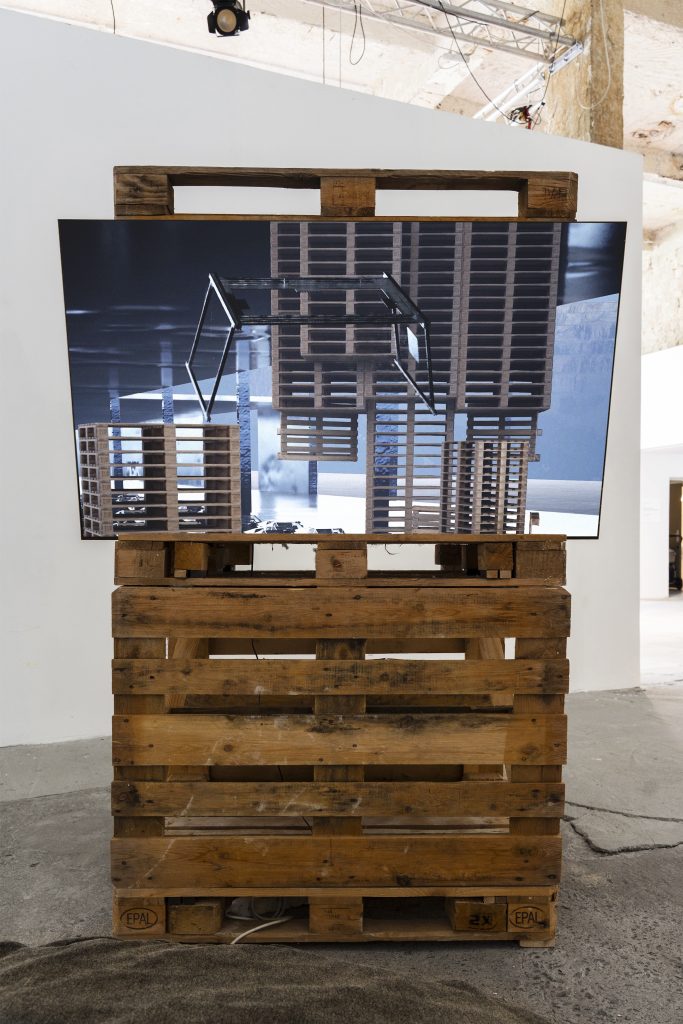

What about the pallets?

In the film, the pallet structure allows for a higher point of view and a better surveillance vantage point, and also serves as a bit of weirding in terms of their placement. Like, why would there be these pallets at a hangar full of $100.000 cars? But the pallets appeared in the installation, too. Rumble premiered in two locations simultaneously; besides OFF, it was exhibited at a group show titled EXOSKELETON in a repurposed factory called Torula in Győr, where I imagined a pallet structure that holds the screen, and the curators of the exhibition carried out this idea so well that the virtual pallet throne in the end was inspired by their construct. Both the metallic body of Window at OFF and this pallet throne served as a gateway, or immersion device, that kind of situated the viewer in this fantasy world.

What’s the significance of weirding in Rumble and your work in general?

Weirding is maybe not the right word for what I usually seek in these stories. I’m drawn to uncertainty, ambiguity, and, in general, the self-contradictory tension that gives these stories their, let’s say, weirdness. These untappable qualities usually emerge from the way I like to stitch distinct things, events, and references together.

Rumble 2025 – Tamás Páll – EXOSKELETON, Torula, Győr. Photo by Zsuzsi Simon

Tell a bit about this extremophile commune from this perspective.

Rumble is part of a series of works about fictional underground communities that I’ve been developing in the past few years. The community that I introduce here is a group of fictional extremophiles. Its members are part-human, part-insect characters that live in extreme environments. When I begin developing a community, I usually start by looking at their environment—where they live and how they interact with that place. From there, I often build on existing underground, subcultural, or online communities, exaggerating certain traits and extending them towards nonhuman characteristics to draw some connections between different ecologies and social forms. This step from human to animal, plant, or infrastructure is usually the first gateway where my stories go beyond realism.

Can you say a few words about the other communities you’ve developed?

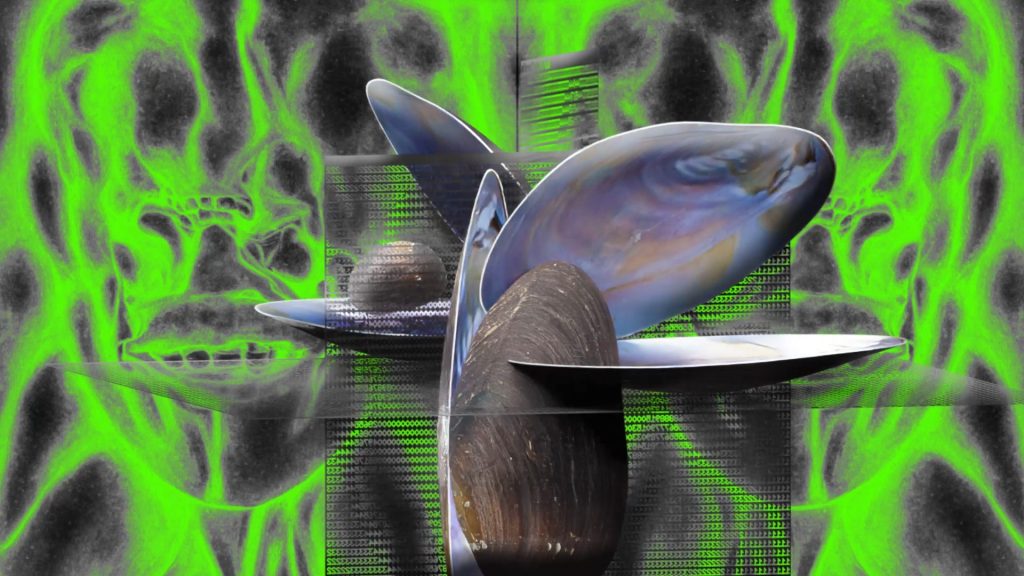

So the series revolves around small groups who squat in spaces that are private, abandoned, or dangerous and create their own small world, their stories, and habits in them. It all started with Lair, where I imagined a community of squatters living in a biodome located in Budapest, which responded to a real scandal and real-estate development project carried out and abandoned by Fidesz, the neoconservative ruling party of Hungary. Since then, I made a chapter (Nesting) that extended Lair’s world with a factory site, where a group of performers create rituals and funerals based on mussels dwelling in industrial and toxic waste disposal sites, while illegally exploring these places. Rumble is the 3rd chapter. I call this series Cycles, and all of its chapters track and reflect on the reindustrialization of Eastern Europe, and how squatting and worlding can hijack imagination to envision different ways of being in and around these industrial, non-spaces.

Tamás Páll – LAIR (2022-23). Photo by Tamás Páll

So you said that weirding is a tool for you to go beyond realism. But what’s happening beyond realism? Is it the place where transformation takes place?

I think my stories oscillate between real-world phenomena and fantasy rather hectically. This comes from the way I do the research for these stories. Usually, I come across a specific story in the news, a building, a character, a technology, an event, or a meme, and that pushes me down into a rabbit hole, where the origin of my interest gets dispersed. In these rabbit holes, I often find another thing that triggers a new association, and so on. I like to bring these references into multiple scales, from personal to planetary, and this is where the associative transformation happens and imagination takes realism’s place. This creates a realism fractal, which on some level, can be read as “true” and on some other levels it is complete fiction. I like this structure because, in some ways, it aligns with how I perceive the world and myself in it unconsciously. For example, my memory is not the best, so I have a habit of fabricating memories. Sometimes from my dreams, sometimes from little lies, sometimes from coping. But maybe this is a bit too personal.

Technically or aesthetically speaking, my works are often very immersive, or have their own visual worlds that are fairly detailed. I like to use forms that could trigger apophenia or pareidolia. This technique brings my fractal relation to reality into an aesthetic experience.

And I also like to play around with the notion of realism, both in aesthetic terms and in referentiality. In Rumble, I combine real-world references like the EU’s agenda to control national mineral mining and the EV industry with completely made-up fantasies like this glowing green extremophile commune.

Tamás Páll – LAIR (2022-23). Photo by Tamás Páll

Window tells a dream unfolding in a lithium mine, which obviously has real-world connotations.

Lithium is a similar element in my view to Window. It condenses multiple threads of reality into one, as it is used in psychopharmaceuticals and electric vehicles; thus, it is the target of interest of industrial development, and it is at the center of attention for multiple nation states and geopolitical policy-making.

For example, the EU has issued an act in 2024 regarding nationalising lithium extraction and production to control the transition to green energy (Critical Raw Materials Act) and the will for independence from China. Part of this act is a lithium mine that was blasted open in Serbia. Lithium mining takes a toll on the mine’s environment, essentially turning local ecologies into dust. The EU backing of the Serbian Jadar mine would clearly signal the need for colonial re-industrialization of both EU members (like the battery factories dropping in Hungary) and non-EU countries to take a handle on the industrial competition.

There are a lot of explosions and fire scenes in the film. Why?

When I zoomed in on the single batteries rather than the infrastructural context—a perspective shift that my film also does—I found multiple cases of fire and explosions of electric and self-driving vehicles using Lithium batteries. Lithium is super volatile, and so is the public opinion and self-expression towards Tesla. There is a TikTok trend with the hashtag “#burntesla” which gathers footage of burning Teslas, where the cars sometimes burst into flames due to faulty tech, but sometimes they are lit on fire purposefully to express feelings about Elon Musk and his ties to the current Trump administration.

I found the part really interesting about world-making based on exploitation. World-making has become such a cool thing to talk about—to the point that it feels a bit overused and emptied out—when it comes to our struggles against oppressive regimes. But here the term also refers to the absurd ways in which dominant powers colonize other people’s realities.

World-making or world-building projects on planetary scales, such as industrial paradigm shifts behind green energy policies, are usually built on the exploitation of people and ecosystems, and this exploitation is often hidden behind grand narratives that frame this process as inevitable, natural, or necessary.

But world-making can also be a method of maintaining a community, nurturing its infrastructure, its stories, and the relationships it emerges from. For example, the Under500 festival [a grassroots contemporary performing arts festival in Budapest that Gyula and Tamás are both the organizers of] is a kind of world-building project in my view, where we carve out our own small pocket in the neoconservative reality of Hungary to nourish art projects, and it builds our art scene and strengthens our community.

In my stories, I often build on this double nature of narratives. In Rumble, Lithium is the character or element that carries this duality. Being one of the softer metals on Earth, it welds together multiple worldviews and phenomena in its core and the narratives surrounding it. I see this as the element’s own way of storytelling, a nonhuman narration that unfolds on a planetary scale and a way of editing that I tried to mimic in Rumble.

According to Window, it is impossible to have a grasp on reality. What does it really mean?

Window is a bit of a trickster character, or at least I like to read it that way. First, it states that it is impossible to have a grasp on reality without becoming a world, and then it tells a story of how it became a world together with the community. It shows the very personal process of this transformation, from its origin story when it was a surveillance system, then how it essentially burst into flames as a self-destructive ritual, and then became one with the Earth, its minerals, and the community. Yet apart from this transformation, there is no story that comes after this transformation, where Window has become the world, and thus it knows reality. One could start doubting the words this character is delivering from the get-go, as it speaks about things that are kind of undoing themselves: To have a grasp on reality, you need to become that very reality.

Nesting – Tamás_Páll, Discotec, 2024

The community “puts a spell” on Window, and that’s how the entire transformation starts. Are they doing this through the way they exist beyond representation, by breaking or hijacking regimes of surveillance and exploitation?

No, it is an active spell. There is one scene where the group is crawling around the surface of a Cybertruck while whispering things to its metal surface. This is the first spell that happens to every technological object within Rumble when they meet the community. This creates a chain reaction that is fueled by the strong connection that emerges between the group and the metal. This chain reaction then becomes almost like a love story, where the worldviews of these surveillance and technological objects are shaken and opened up for an undoing, and then become anew together with the community. This spell is a world-welding act that happens somewhere between human and object.

What does it mean on a rather personal level—in our everyday lives—that it’s impossible to have a grasp on reality?

Personally, I feel like I explode into a million pieces when I try to unpack the threads of the world. Living in a world that is grasped mainly through narratives and language makes it very hard to have a sense of common ground with the world outside of reach. This uncertainty is often a driving force in my stories, as these works are often fractalized sense-making projects of tendencies I encounter in the world.

Your work, in a way, suggests that there is a solution for this “problem,” and it has to do with the irrational and the intangible. You are saying that when one becomes the world, it is a moment of revelation, and in this moment, you become inhuman, and everything you are becomes a rumble.

Rumble indeed has a pull towards the irrational. The main score of the story is the mantra of the group that triggers the transformation of Window. While the mantra is not directly shown throughout the film, its effects on Window’s perception of reality are sketched out in the aesthetic shifts in the film as a sort of vibration between different perspectives and realities.

Becoming the world is in part a metaphor for the unreal struggle to process the world as a whole, universal, singular reality that can be understood by one perspective, religion, rationality, or something else. This is a view that Window embodies before its transformation. From another perspective, this becoming is only possible through undoing the self, shedding the skin that was imposed upon you—the models, assigned roles, and the world that you carry with yourself since you were born. Through this undoing, Window’s old self and purpose of being a surveillance system dissolve, and it becomes elemental, part lithium, part human, and part a burnt truck.

Tamás Páll – LAIR (2022-23). Photo by Tamás Páll

Our collaborations in Hollow, where we work a lot with larp, performance, sound, and immersive technologies, clearly show that this becoming and the undoing of the self are important to you also in aesthetic terms. I personally think that corporeal experiences have a bigger chance of inducing change in one’s reality than, let’s say, a visual art exhibition, and that’s what pulls me—a person who initially identified as a contemporary art curator—towards dance and immersive performance. What are your thoughts on that?

In the past 10+ years, I have always been drawn towards time-based, live, or network media and art. I think this affection towards liveness comes from my need to experience different forms of being. Working with these media that you listed, both with Hollow and in my individual practice, allows me to experiment with processes and settings that I couldn’t imagine before. Situations and stories often emerge from working together with an audience or with other artists—I think this procedural unfolding is what still drives me to do art.

At the same time, I also see that individually, you are getting back to video and film. Why is that?

Video has always been a core medium in my practice, but recently I’ve become interested in how content creation is shifting and how the context and spaces of consuming content (e.g., 4/5D cinema, screen experiences, etc.) accommodate this shift. This interest also pushes me towards deconstructing how I view content online or in a movie theater, and how a video can extend in the physical space, or how I formed connections with screens, or, for instance, what live performance can do to this relation to screen-based media and vice versa.

Would you like to share anything about the projects you are currently working on?

Last year, I started working on Dreamwork, which is a video series, where I collaborate with performance artists working with alter-egos. The individual chapters are part documentary and part fiction, departing from the stories and dreams the artists tell on set, and the series as a whole will form a fictional dream realm where the alter-egos create an alternate reality. I just finished shooting the second episode with Claywoman, a persona created by experimental theater maker and performance artist Michael Cavadias from New York, and I’m currently editing the first chapter that features Nicole Clore, the drag character of Hungarian dancer and choreographer Csaba Molnár. The premiere will be in the fall in Budapest. And, as you know, we will also start touring with Hollow in November [with their latest performance titled Baby, which is a piece investigating group dynamics, AI, BDSM, and the queering of family].

Text: Gyula Muskovics

Lead image: Rumble 2025 – Tamás Páll – film still

Credits

Rumble (2025)

Directed by Tamás PÁLL

Movement by Luca KANCSÓ

Pallett Installation construction by Luca PETRÁNYI

Tamás PÁLL is an interdisciplinary artist from Budapest, working with digital media, video games, installation, and performance. His praxis blends experimental game design, film, writing, installation, role-play, performance, and mythopoesis. Tamás’ works are assemblages of associations and embodied experience that weave together the politics of technology and Eastern Europe, online subcultures, scientific world-views, non-human storytelling, and synthetic mythologies into his vessels of research. He is a co-founder of the art collective Rites Network and the artist group Hollow. His projects have been showcased in numerous venues, including The Victoria & Albert Museum, London; ISCP and Residency Unlimited New York; Art Cologne; Panke Gallery, Berlin; Transmediale, Berlin; MeetFactory, Prague; Ludwig Museum, Budapest, Trafó House of Contemporary Arts, Budapest, among others.

Gyula MUSKOVICS is a curator, writer, artist, and researcher oscillating between Budapest and New York. In 2023 and 2024, he was a Fulbright fellow at The Museum of Modern Art and New York University. His works and publications are motivated by a pull towards the edge and revolve around subversion, queer desire, intimacy, and the political capabilities of the body. He earned a PhD in Art Theory at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in Budapest in 2025 with a dissertation on the avant-garde fashion circles of the former Eastern Bloc. His writings have been published in the European Journal of Women’s Studies, DIK Fagazine, CTM Magazine, Momus Journal, Artmargins, and post-MoMA.

Gyula and Tamás formed their artist group Hollow with choreographer Viktor SZERI in 2018. They realize immersive performances and installations that merge the methodologies of dance, poetics, augmented reality, and live action role-playing to build world prototypes where the dominant systems of consensual reality can be questioned and modified.

This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthening the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union (EU) or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the EU nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.